SIMONOV, KONSTANTIN (KIRILL) MIKHAILOVICH(1915-1979) - poet, prose writer, playwright, journalist, editor, public figure.

Born November 28, 1915 in Petrograd in the family of Colonel of the General Staff Mikhail Agafangelovich Simonov and Princess Alexandra Leonidovna Obolenskaya (second marriage - A.L. Ivanisheva).

Simonov's father went missing during the Civil War.

In 1919, the mother and son moved to Ryazan, where she married a military specialist, a teacher of military affairs, a former colonel of the tsarist army, A.G. Ivanishev. By Simonov's own admission (see his poem Father), his stepfather had a strong and beneficial influence on his life and everyday principles and habits. He owes his lifelong love to the army to his stepfather.

He studied in Ryazan, and graduated from the eight-year school in Saratov, where his stepfather was transferred. After seven years, he continued his education at the FZU, having moved with his parents to Moscow, he worked as a turner in the workshops of Mezhrabpomfilm on Potylikh (now Mosfilm), and in 1934 he entered the Literary Institute, where he studied in the seminars of P. Antokolsky and V. Lugovsky. His fellow students were E. Dolmatovsky, M. Matusovsky, M. Aliger.

Simonov's poetic biography developed successfully and fruitfully. Even before admission to the Literary Institute, he, as a young working author, was given a business trip to build the White Sea Canal, as a result of which a poem appeared Pavel Cherny, perhaps the most "engaged" of his poetic works. Collection of poems (together with Matusovsky) Luhansk residents, poems Winner, Battle on the Ice and Suvorov– publications of a literary institute student. They already showed the strengths of Simonov's talent - historicism, close to colloquial naturalness of intonation, romantic pathos of duty, male friendship, soldier's brotherhood, unostentatious patriotism.

Simonov announced himself loudly and immediately. The first poem that brought him fame already outside the "narrow circles" was the poem General, dedicated to the memory of Mate Zalk, who created one of the most enduring legends of Simonov's biography - about his participation in the war in Spain.

In the early autumn of 1939, Simonov went to his first war - he was appointed poet to the Heroic Red Army newspaper on Khalkhin Gol. Shortly before leaving for the front, he finally changes his name and instead of the original Kirill takes the pseudonym Konstantin Simonov. The reason for this is the most ordinary: without pronouncing "r" and a hard "l", it is difficult to pronounce your own name. The pseudonym becomes a literary fact, and soon the name Konstantin Simonov gains popularity.

At Khalkhin Gol, the first "run-in" of the war took place. The foundation of a military writer and journalist was formed, which Simonov will remain for life: admiration for military professionalism, respect for the courage of the enemy, mercy for the defeated, loyalty to front-line friends, military duty, disgust for weaklings and whiners, emphasized hussar attitude towards women.

In a poem Tank, written on Khalkhin Gol, Simonov sees the symbol of victory in a Soviet tank mangled in battle and offers this tank as a Victory monument.

At Khalkhin Gol, Simonov's life included people to whom he remained faithful until his last days. This is, first of all, the then young, but already legendary G.K. Zhukov and the editor of the Heroic Red Army, and in the Great Patriotic War - the Red Star, David Ortenberg, who later became the heroes of his memoirs and the prototypes of the characters in his prose.

It was at Khalkhin Gol that Simonov's talent "matured", where he turned from a promising young writer into a poet and a soldier.

Between the two wars, he first tried his hand at dramaturgy. And if the first play One love story did not bring him magnificent laurels, then the second - Guy from our city, completed on the eve of the Great Patriotic War, for several decades entered the repertoire of the best domestic theaters.

From the first days of the Patriotic War, Simonov was on the Western Front. Before the newspaper, to which he was appointed war correspondent, he never got.

On July 13, in a field near Mogilev, he ended up at the location of the 388th Infantry Regiment, which dug in according to all the rules of military art and stood there to the death, not thinking about retreat. This tiny island of hope in the midst of an ocean of despair is strongly and forever imprinted in the writer's memory. It is on this Buinichsky field in the novel Living and dead two favorite Simonov's heroes will meet - Sintsov and Serpilin. On this field, Simonov bequeathed to dispel his ashes after his death.

Having miraculously escaped encirclement, he returned to Moscow. In the future, he spent the entire war as a correspondent for the Red Star. He became one of the best military journalists - he went on a submarine to the Romanian rear, with scouts - to the Norwegian fjords, on the Arabat Spit - to attack with infantry, saw the whole war from the Black to the Barents Sea, ended it in Berlin, was present at the signing of the act of surrender Nazi Germany and remained a military writer, chronicler and historian of this war for the rest of his life. I always remembered and very often repeated two maxims learned in the war: that one person cannot know the whole war, and therefore it always - everyone has his own, and that a war correspondent is a difficult and dangerous profession, but far from the most difficult and certainly not the most dangerous at war.

During the war, Simonov's lifestyle was also formed, the basis of which was efficiency, composure and purposefulness. During the four war years - five collections of essays and short stories, a story Days and nights, plays Russian people, So be it, Under the chestnut trees of Prague, diaries, which subsequently made up two volumes of his collected works, and, finally, poems, which since February 1942, after being published in Pravda Wait for me, expected literally the entire warring country.

Phenomenon Wait for me, cut out, reprinted and rewritten, sent home from the front and from the rear to the front, the phenomenon of a poem written in August 1941 at someone else's dacha in Peredelkino, addressed to a very specific, earthly, but at that moment - distant woman, goes beyond poetry. Wait for me- the prayer of an atheist, the incantation of fate, the fragile bridge between life and death, and it is also the support of this bridge. It predicts that the war will be long and cruel, and it is guessed that man is stronger than war. If he loves, if he believes.

In the same 1941, a poem was written It's like looking through binoculars upside down...- which, according to the author himself, "having written", frightened him with his frank desire to rethink and re-evaluate much of what preceded this war.

We, having gone through blood and suffering,

Let's look back at the past again.

But on this distant date

Let us not stoop to our former blindness.

The twenty-nine-year-old Simonov met the victory as a famous writer, winner of the Stalin Prizes, the youngest of the leaders of the Writers' Union, the author of famous poems, plays, prose, translated into different languages.

The time of the war was sometimes a happy coincidence of official ideology and his own worldview, his own hopes and common faith. But immediately after the victory, a growing contradiction began to emerge between Simonov's official visible successes and his work. Editor of Novy Mir, deputy of the Supreme Council, editor of Literaturnaya Gazeta, member of the World Peace Council, trips - Japan, America, London, Paris, Prague, meetings with Chaplin and Beth Davis, with Bunin and Neruda, and poetry - almost journalism , under Mayakovsky, where even the most successful are equipped with rhetorical ideologies.

He was threatened with a shift in the internal moral guidelines that distinguish talent from mediocrity. The then criticism also contributed to this, when for an opportunistic play on a plot suggested by the leader, - alien shadow- he received another Stalin Prize, and a modest but sincere story about the Smolensk region, exhausted by the war Homeland smoke subjected to devastating criticism.

The best he has written over the years is a novel Comrades in arms- the forerunner of his famous military trilogy - Simonov, who did not like to edit published works, in subsequent years he reworked it repeatedly and reduced it almost three times.

Stalin's death coincided with changes in his personal and creative life: Simonov divorced actress Valentina Vasilievna Serova, married the widow of the poet Semyon Gudzenko Larisa Zhadova, was removed from the editorship of Novy Mir, and in 1958 left for Tashkent as Pravda's own correspondent in the Middle Asia.

Here, at a relative distance from political and literary battles, he wrote Living and dead. The liberal air of the "thaw" () and a magnificent, detailed and sensual knowledge of the war were happily combined in this prose. Separated from the novel and published separately stories Panteleev and Levashov- perhaps the best that Simonov wrote about the war.

Comparing the diaries published later with the prose written earlier, it is easy to see that Simonov sends his heroes to where he himself was, endowing them with his military experience, his impressions. This gives rise to a deceptive feeling that the characters themselves are autobiographical, especially since two of them are Sintsov in the trilogy and Lopatin in The so-called private life- military journalists. Simonov repeatedly and publicly, and most importantly, justifiably, protested against such identification. Both the advantages and disadvantages of Simonov's prose stem from its completely different, root quality: he wrote the characters not as he was, but as he himself would like to be. They were cleaner, straighter, nobler, more consistent than himself.

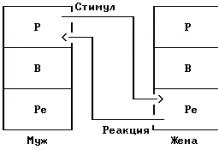

Simonov's prose is male prose. One of the paradoxical and vivid examples of this is the female images - the characters of the heroines whom he loves, to whom he gives his unconditional male sympathy. All of them are variations of the lyrical heroine Wait for me- and poems, and plays, and films. With a variety of destinies, guises and life circumstances, these are women endowed with masculine consistency in actions and special fidelity and the ability to wait. Varya in Guy from our city, Masha and the little doctor in The living and the dead, many other female images relentlessly follow this Simonovian ideal.

Simonov's war is voluminous, he sees it from different points and angles, moving freely in its space from the trenches of the front line to army headquarters and the deep rear. Quite often, Simonov was reproached for the fact that his prose is officer-like, that it is devoid of the blood and sweat of daily soldier labor. Even if this is so, it is because every line of his prose has been verified by Simonov's military experience, and loyalty to this principle held back the writer's imagination.

Simonov returned from Tashkent to Moscow in the early 1960s, at the end of the "thaw" mood. Character Fact: Movie Living and dead was loved by the author and was considered the pride of the national cinema, and the film, shot three years later, based on the second part of the novel - Soldiers are not born- underwent such destructive editing that the author was forced to remove his last name from the credits and the film was released under the title Retribution and is now forgotten, although the cast there is no less stellar and the direction in both films is the same.

The time of "stagnation" noticeably affects Simonov's work: he hardly writes poetry, and some poetic successes are directly related to the past - the war, its memory, its historical dates. His last play Fourth- there is a lack of inner freedom, and despite the premieres in the two best theaters at that time - Sovremennik in Moscow and the Bolshoi Drama Theater in Leningrad, the play did not become an event in dramaturgy, and even more so in public life. The work on the continuation of the novel, which took almost eight years, also progressed with difficulty. Soldiers are not born and last summer, which concludes the trilogy, with all its merits and successes, is noticeably inferior to Alive and dead.

However, Simonov takes revenge on the literary-historical field. Having spent several years of his life carefully and in detail tracing and comprehending the fate of people and events that are captured in his military diaries, he is preparing a book for publication. One Hundred Days of War, where diary entries from 1941 are interspersed with later reflections and comments. Simonov himself was inclined to consider this book the best of all he had written. Military historians and many literary critics agree with this. The book was typed in the last three issues of Novy Mir for 1967, but it only saw the light of day more than seven years later, and even then with huge losses, tormented by military censorship. None of Simonov's books had such a dramatic fate. And this was connected with the two basic components of this work, with the very principle of its stereoscopicity. The war is seen in the book up close - in the diaries and notes of 1941 and from a distance of a quarter of a century - in comments and reflections.

About his unwillingness to retroactively correct works written during the war years, Simonov himself wrote: “... if they can give the reader some idea of this complex, contradictory time that included four years of war against fascism, then it is in the form in which they were written by me then. And he implemented this principle in preparation for the publication of diary entries. The tragedy of the first months of the war looks in the diaries as it was in reality - a national disaster.

The rethinking of the role of Stalin also turned out to be a reason for censorship intervention. “One of the most tragic features of the past era, associated with the concept of the “cult of personality,” wrote Simonov in the preface to his first six-volume collected works, published in 1966, “is the contradiction between what Stalin really was and how he seemed to people. And it is hardly worth softening this tragic contradiction, already firmly fixed in our minds.

The path of official recognition and latent "disgrace" becomes Simonov's lot for all his remaining years. He slowly but surely moved through the stages of state recognition of merit: he received the Lenin Prize for the trilogy Living and dead, the title of Hero of Socialist Labor on his sixtieth birthday, was elected to the highest party bodies, sat on the presidium, secretaried in the joint venture and headed various commissions. He had every reason to lull himself with these testimonies of the goodwill of the party and the government. The glory of the Soviet writer was well-deserved and ... joyless.

He was offered to head a serious magazine only once, when it was necessary to put an end to Novy Mir and remove Tvardovsky from the leadership. Simonov flatly refused, saying that the only thing he was ready for was to go to Tvardovsky's deputy, if he deems it necessary.

Deprived of the opportunity to realize his editorial ideas, to really influence the mechanisms of the literary process, Simonov realizes all his enormous human potential in the area that is commonly called the "theory of small deeds." He embodied his unexpended forces on his own literature in many deeds and deeds that restore or establish justice and truth in the face of resisting tendencies in social and literary life.

Return to the reader of the novels of Ilf and Petrov, the publication of Bulgakov's Masters and Margarita and Hemingway For whom the Bell Tolls, defense of Lily Brik, which high-ranking "historians of literature" decided to delete from Mayakovsky's biography, the first complete translation of the plays by Arthur Miller and Eugene O "Neill, the publication of the first story by Vyacheslav Kondratiev Sasha- this is a far from complete list of "Hercules feats" of Simonov, only those that achieved the goal and only in the field of literature. But there were also participation in the “breakthrough” of performances at Sovremennik and the Taganka Theater, the first posthumous exhibition of Tatlin, the restoration of the exhibition “XX Years of Work” by Mayakovsky, participation in the cinematic fate of A. German and dozens of other filmmakers, artists, writers. Not a single unanswered letter. The dozens of volumes of Simonov's daily efforts, stored today in TsGALI, named by him All done contain thousands of his letters, notes, statements, petitions, requests, recommendations, reviews, analyzes and advice, prefaces, paving the way for "impenetrable" books and publications. Simonov's comrades in arms enjoyed special attention. Hundreds of people began to write military memoirs after Simonov read and sympathetically evaluated "pen trials". He tried to help the former front-line soldiers solve many everyday problems: hospitals, apartments, prostheses, glasses, unreceived awards, unfinished biographies.

Literary and artistic work continued. Little stories From the notes of Lopatin gradually formed into the last Simonov novel The so-called private life. In 1976 they were published in two volumes. Different days of the war where mangled censored One hundred days were supplemented by diaries 1942-1945 and related comments.

For the past decade, he has also been involved in cinematography. Together with Roman Karmen he created a film poem Grenada, Grenada, my Grenada, then independently, as the author of the film Someone else's grief does not happen about the Vietnam War There was a soldier, Soldier's memoirs- based on conversations with holders of the three Orders of Glory, TV films about Bulgakov and Tvardovsky.

August 28, 1979 Konstantin Simonov died. The official obituary said: "The date of the funeral at the Novodevichy Cemetery will be announced separately." Did not take place. Simonov bequeathed to scatter his ashes on the field near Mogilev, the most memorable place of his life. The fact that his ashes were scattered, the message could not appear in the press for more than a year. On the official memorial plaque near Simonov's office on Chernyakhovsky Street, it is written: "Hero of Socialist Labor." On a stone near the Buynichesky field: "All his life he remembered this battlefield and bequeathed to dispel his ashes here."

Compositions: K.Simonov. Collected works in 12 volumes, publishing house of Artistic Literature, 1978–1988.

Konstantin Simonov was not only a great writer, but also a screenwriter, journalist and active public figure. He went through the entire Great Patriotic War, participated in the battle of Khalkhin Gol. He was a colonel in the USSR army. His biography is bright, colorful, full of memories, hopes, accomplishments.

The biography of Konstantin Mikhailovich began on November 15, 1915, when the writer was born in the city of Petrograd in the family of a military man and a princess. However, he never saw his father in his life: he was listed as missing in the First World War. In 1919, the mother moved with her child to Ryazan, where she remarried a military teacher.

Konstantin's childhood and youth were spent in military camps. He was raised by his stepfather. After school, the guy entered the school, then got a job as a turner at the factory. In 1931, together with his whole family, he moved to live in Moscow.

In 1938, Konstantin Simonov graduated from the literary institute, but by this time he had already written several of his own works. Interestingly, at birth he was given the name Cyril, but later the writer decided to change it and took the pseudonym Konstantin Simonov.

With the outbreak of the war, the writer is sent to the front as a war correspondent, he goes through the entire war from beginning to end, happens in many cities under siege and "hot spots". Several times he was nominated for awards. At the end of the war, all its difficulties and horrors were described in his works.

Konstantin Simonov passed away in August 1979. The cause of death was cancer. The ashes of the writer were scattered over the Buinichi field in accordance with his will.

In his life, Konstantin Simonov was officially married four times. His first wife was Natalya Ginzburg, also a writer. It is to her that the poem "Five Pages" is dedicated.

The second wife of Konstantin Mikhailovich was Evgenia Laskina, a philologist and literary editor. In 1939, the son Alexei was born to the family. However, already in 1940, Simonov broke up with Evgenia and became interested in actress Valentina Serova, who gave him a daughter, Maria, in 1950.

His last official wife was Larisa Zhadova, an art critic. By the time of their marriage, Larisa already had a daughter, Catherine, whom Konstantin adopted. A little later, a joint daughter, Alexander, was born in the family. After her death, Larisa also bequeathed to scatter her ashes over the Buinichi field in order to be near her husband.

Categories Tags:The article tells about a brief biography of Konstantin Simonov, a famous Soviet journalist and writer, who became famous primarily for his works about the Great Patriotic War.

Biography of Simonov: the first years

Konstantin Mikhailovich Simonov was born in 1915 in Petrograd. He was raised by his stepfather, a professional soldier. The life of the family was strictly subordinated to the army routine. Thanks to this, Simonov acquired discipline and forever retained in his soul a deep respect for the military profession. The future writer began his working life as a simple worker, became a turner. Since 1931, Simonov and his family have been living in Moscow, where he works at a factory. At this time, he began to write poetry, which appeared in print since 1934. Simonov's first poem, "Pavel Cherny", sang the heroism of the participants in socialist construction.

Simonov graduated from the Literary Institute and wanted to continue his studies, but in 1939 he was sent to Mongolia as a war correspondent. This profession became the main one for the writer during the Great Patriotic War. Covering the events at Khalkhin Gol, Simonov speaks with sympathy about the enemy in verse, notes the heroism of the Japanese.

Before the war, Simonov published several collections of poems and began work as a playwright. Then he became a member of the Writers' Union.

Biography of Simonov during the war years

Throughout the war, the writer is engaged in titanic work, combining the work of a correspondent on the most intense sectors of the fronts with literary activity. Simonov seeks to get into the most dangerous places of hostilities. His chronicle of the war years became the basis for many outstanding works ("Russian People", "Days and Nights" and many others).

A special place in the literary activity of Simonov is occupied by the poem "Wait for me". It was so popular that newspaper clippings with the text of the poem were found in the breast pockets of dead soldiers. He was carried with him at the heart, as a great shrine. The poem was memorized. It became the personification of the hope and faith of millions of Soviet soldiers.

Simonov's poems, dedicated to the war and written by a direct witness, enjoy great love among Soviet soldiers. The writer communicates with the heroes and ordinary participants in the war, takes numerous interviews. Primitive agitation is not characteristic of his works, they reflect the harsh truth of the war, which is how they find their way to the hearts of many readers. Simonov openly expresses the views of the soldiers on the causes of military failures, their bitterness from the defeats of the first years. The writer is credited for describing the capture of territories recently abandoned by the Nazis. In these observations, the author is struck by the naked pain at the sight of the suffering and misfortune of the enslaved population.

The writer went through all the fronts of the war, took part in the capture of Berlin. Simonov witnessed the signing of the act of unconditional surrender of Germany.

Simonov's biography after the war

After the war, the writer made a large number of trips abroad, accompanied by speeches and lectures. He certainly fully shared the Soviet ideology, but he was looking for a way to establish normal relations with the Western world.

In 1952, Simonov published the novel Comrades in Arms. In subsequent years, he worked on the trilogy "The Living and the Dead". Simonov was the author of the script for several films that received wide recognition and popularity. At the same time, the writer was engaged in a wide public activity, was the editor-in-chief of a number of major Soviet publications.

The writer was a pronounced Stalinist, but after Khrushchev debunked the cult of personality, he somewhat moved away from his former irreconcilable positions. This was reflected in the works of Simonov, where the mistakes of the leadership in the field of military operations began to be more clearly indicated.

Simonov died in 1979. According to the writer's own will, he was cremated and his remains scattered over the most expensive for Simonov areas of hostilities.

Konstantin Mikhailovich Simonov has a rather rich biography. This man did not forget about literature even during the Second World War. During his life he managed to do a lot and left a mark for his admirers.

1. The real name of Konstantin Mikhailovich Simonov is Kirill.

2. This writer did not know anything about his father, because he went missing during the First World War.

3. From the age of 4, Simonov and his mother began to live in Ryazan.

4. The first wife of Konstantin Mikhailovich Simonov was Natalya Viktorovna Ginzburg.

5. The writer dedicated a beautiful poem to his wife called “Five Pages”.

6. Since 1940, the writer was in love with actress Valentina Serova, who at that time was the wife of brigade commander Serov.

7. Love was the main inspiration for the writer.

8. The last wife of Simonov is Larisa Alekseevna Zhadova, from whom he had a daughter.

9. The first poems of Konstantin Mikhailovich Simonov were published in the publications "October" and "Young Guard".

10. Simonov chose a pseudonym for himself because it was difficult for him to pronounce his name Kirill.

11. In 1942, the writer was awarded the title of senior battalion commissar.

12. After the end of the war, Simonov already had the rank of colonel.

13. The mother of Konstantin Mikhailovich Simonov was a princess.

14. The father of Konstantin Mikhailovich Simonov was of Armenian origin.

15. In childhood, the future writer was brought up by his stepfather.

16. The writer spent his childhood in commander's dormitories and military camps.

17. Simonov's mother never recognized his pseudonym.

18. Konstantin Mikhailovich Simonov died of cancer in Moscow.

19. In his youth, Simonov had to work as a metal turner, but even then he had a passion for literature.

20. Konstantin Mikhailovich Simonov is considered the winner of six Stalin Prizes.

21. Despite the fact that his stepfather treated the future writer strictly, Konstantin respected and loved him.

22. Simonov was able to combine two professions into one: military affairs and literature. He was a war correspondent.

23. Konstantin Mikhailovich wrote his first poem in the house of his own aunt of a noble family, Sofya Obolenskaya.

24. In 1952, Simonov's first novel with the title "comrades in arms" was presented to the people.

25. Konstantin Mikhailovich Simonov became in demand only in the 40-50s.

26. Only 7 people took part in the farewell ceremony for the great Soviet writer: a widow with children and local historians from Mogilev.

27. In the post-war years, Simonov had to work as an editor in the Novy Mir magazine.

28. This writer did not have a drop of respect for Solzhenitsyn, Akhmatova and Zoshchenko.

29. The first wife of Konstantin Mikhailovich Simonov was from a highly respected noble family.

30. When the second wife of Simonov, with whom he lived for 15 long years, died, he sent her a bouquet of 58 roses.

31. After the death of the writer, his body was cremated, and the ashes were scattered over the Buinichsky field.

32. Until 1935, Simonov worked at the factory.

33. After the war, Konstantin Mikhailovich Simonov visited the USA, Japan and China.

34. The writer had a speech defect.

35. Films were made according to the scripts of most of the works of this creator.

36. Shortly before his own death, Simonov managed to burn all the records that had anything to do with the painful love for Serova.

37. The most touching poem from Simonov's work was dedicated specifically to Serova.

38. Konstantin Mikhailovich Simonov had to treat his wife Valentin Serov for alcoholism.

39. The writer's stepfather participated in the German and Japanese wars, and therefore the discipline in their house was severe.

40. Simonov was considered the first person who began to study captured documents and extracted reliable information from them.

41. When Simonov's wife died, he rested in Kislovodsk.

42. At the Gorky Literary Institute, the future writer received a successful education.

43. Simonov's service began at Khalkin Gol, where he met Georgy Zhukov.

44. It was Simonov's first wife who insisted on the publication of Bulgakov's The Master and Margarita.

45. At the age of 30, Simonov finished fighting.

46. Konstantin Mikhailovich Simonov was present at the signing of the act of surrender of enemy Germany.

47. Konstantin Mikhailovich gave a harsh assessment of Stalin.

48. Simonov was considered the only Soviet writer who gave answers to every letter.

49. In addition to the fact that Konstantin Mikhailovich Simonov was a writer, he was also considered a screenwriter of that time.

50. The stepfather of the writer who raised him was a teacher.

Konstantin Simonov is a famous poet, writer, screenwriter, playwright, public figure and journalist. He was born in St. Petersburg on November 28, 1915. As a child, he lived in Saratov and Ryazan. His stepfather Alexander Ivanishev, who taught military tactics at the school, was engaged in his upbringing. In 1930 Konstantin finished school. Then he began to study as a turner. In 1931 the family moved to Moscow. Simonov graduated from the Faculty of Precision Mechanics. Until 1935, his place of work was an aircraft factory. In Mezhrabpomfilm he works as a technician and at the same time tries to write poetry. In 1934, the works of Konstantin Simonov were published for the first time.

Simonov's biography in his younger years is quite extensive. He received his higher education at MIFLI and the Literary Institute. M. Gorky (1938). He worked as an editor in the "Literary newspaper". After he graduated from the Literary Institute, he decided to enter graduate school at the Institute of History, Philosophy, and Literature. He did not finish his postgraduate studies, he went to Mongolia for Khalkin Gol as a war correspondent. It was 1939. He never returned to school.

"The Story of a Love" is Simonov's first play, he wrote it in 1940. The premiere took place at the Lenin Komsomol Theatre. Then, throughout the year, he takes courses as a war correspondent at the Military-Political Academy, after graduation he was awarded the military rank of quartermaster of the second rank.

During the Second World War, Konstantin was a personal correspondent for several newspapers (Komsomolskaya Pravda, Krasnaya Zvezda, Battle Banner, Pravda, etc.). In 1942 he received the rank of senior battalion commissar, and in 1943 he was promoted to the rank of lieutenant colonel. Then he received the rank of colonel, this was already after the end of the war. Simonov traveled to Romania, Yugoslavia, Bulgaria, Germany, Poland to work as a military journalist. He happened to be an eyewitness to the fighting in Berlin.

In 1942, the first black-and-white film was shot based on the novel by K. Simonov "A guy from our city". The war ended, and for three years he was on business trips to the United States, Japan and China. From 1950 to 1954 he was appointed to the post of editor of the Literaturnaya Gazeta, and from 1954 to 1958 - of the Novy Mir magazine. His activities as a correspondent were continued in Tashkent from 1958 to 1960. There he was a journalist for the newspaper "Pravda" in Central Asia. He wrote his first novel in 1952 called Comrades in Arms. One by one, plays were written (10 in total) from 1940 to 1941.

On August 28, 1979, Konstantin Simonov died in Moscow. Before his death, he said that his ashes should be scattered in places significant for him during the Great Patriotic War. The posthumous wish of the writer and journalist was fulfilled.

Political activities of Konstantin Simonov:

1942 - member of the CPSU;

1952-1956 - his candidacy was considered in the Central Committee of the CPSU;

1956-1961 and 1976 - one of the members of the Central Committee of the CPSU;

1946-1954 - Deputy in the Supreme Soviet of the USSR of the second and third meetings;

1946-1954 - in the management of the Union of Writers of the USSR is an assistant to the general secretary;

1954-1959 and 1967-1979 - already a secretary, not an assistant;

1949 - member of the bodies of the Soviet Committee for the Protection of Peace;

For his professional political activities, Simonov was awarded medals and orders, including three Orders of Lenin. He received the Lenin Prize and the Stalin Prize of the USSR.

We draw your attention to the fact that the biography of Konstantin Mikhailovich Simonov presents the most basic moments from life. Some minor life events may be omitted from this biography.