Years of life : 1551 - 13 April 1605 .

Years of government: Tsar and Grand Duke of All Russia (February 21, 1598 - April 13, 1605).

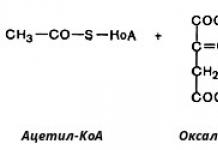

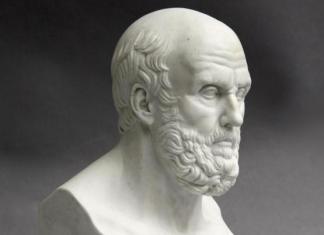

Born around 1551, ascended the throne on February 21, 1598, died on April 13, 1605. The Godunov family, along with the Saburovs and the Velyaminov-Zernovs, descended from the Tatar Murza Chet, in the baptism of Zakharia, who left the Horde to the Grand Duke of Moscow Ivan Danilovich Kalita and built the Kostroma-Ipatiev Monastery. The older line of descendants of Chet, the Saburovs, at the end of the 15th century had already taken a place among the noblest families of the Moscow boyars, while the younger one, the Godunovs, advanced a century later under Grozny, during the oprichnina. Boris began his service at the court of Grozny: in 1570 he was mentioned in the Serpukhov campaign as a bell at the royal saadak (a bow with arrows). In 1571, Boris was a friend at the wedding of the tsar with Marfa Vasilievna Sobakina. Around 1571, Boris strengthened his position at court by marrying the daughter of Malyuta Skuratov-Belsky, Marya Grigoryevna. In 1578, Boris was already a kravchim, and when in 1580 Grozny chose Boris's sister, Irina, as the wife of Tsarevich Fedor, Boris was granted a boyar. In 1581, in a fit of anger, the tsar struck his eldest son Ivan with a mortal blow. There is news that Godunov stood up for the prince and was wounded by Grozny; Boris' opponents informed the tsar that Boris was only pretending to be ill, but Tsar Ivan, having visited the sick man at home, found out the truth and punished the slanderers. After the death of Grozny, with his weak successor, the boyars gained great importance, the largest figures in which were Nikita Romanovich Yuryev, Fyodor's maternal uncle, the well-born, but narrow-minded Prince Ivan Feodorovich Mstislavsky, Prince Ivan Petrovich Shuisky, who became famous for the defense of Pskov from Batory, and close lately, Bogdan Yakovlevich Belsky to the Terrible, to whom, as they say, John entrusted his youngest son Dimitri to guardianship; they were not unanimous, a hidden struggle of the first three against Belsky began. Fearing intrigues in favor of Tsarevich Dimitri, the rulers immediately after the death of Grozny removed the young prince with his mother and her relatives Nagimi to Uglich, who had been assigned to Dimitri by his father. Some kind of popular movement in April, directed against Belsky, served as a pretext for his expulsion: he was sent as governor to Nizhny Novgorod.

Boris, the brother-in-law of the tsar, was showered with favors at the royal wedding on May 31, 1584: he received the noble rank of equestrian, the title of a close great boyar and governor of the kingdoms of Kazan and Astrakhan, land along the river. Volga, meadows on the banks of the river. Moscow, as well as various government fees. But he did not yet enjoy special influence at that time. Only when (in August 1584) Nikita Romanovich fell dangerously ill, and died the following year, entrusting his children to Boris's care and taking an oath from him to be in a "testamentary alliance of friendship" with the Romanovs, did Boris come to the fore. Having on his side businessmen - the Shchelkalovs and the new palace nobility - the Godunovs and Romanovs with their circle, Boris found himself at the head of a strong party. The princes Ivan Fedorovich Mstislavsky, the Shuiskys, the Vorotynskys, the boyar families of the Kolychevs, Golovins, and others constituted a party hostile to Boris. The struggle went on for a long time, but victory leaned towards Boris. As early as the end of 1584, the Golovins fell into disgrace; in the summer of 1585, the old prince Mstislavsky was forcibly tonsured in the Cyril Monastery. The princes Shuisky remained at the head of the opposition. In order to undermine the power of Boris at the root, they, having on their side Metropolitan Dionysius, part of the boyars, nobles and many Moscow merchants, were going to file (in 1587) the tsar with a petition for a divorce from the childless Irina and entering into a new marriage "for the royal sake of childbearing" . The king, who loved Irina very much, who, moreover, was not barren, was greatly offended. The case ended with the exile of the Shuiskys, the overthrow of Metropolitan Dionysius and, in general, the disgrace of their supporters. In place of Dionysius, Archbishop Job of Rostov, a man devoted to Boris, was consecrated as metropolitan.

The elder Shuiskys - Ivan Petrovich and Andrei Ivanovich - died (or were killed) in exile. Now Boris had no more rivals: he had achieved such power as none of his subjects had. Everything that was done by the Moscow government was done at the will of Boris; he received foreign ambassadors with royal pomp and ceremony, corresponded and exchanged letters with foreign sovereigns: the Caesar (Emperor of Austria), the Queen of England, the Crimean Khan, and others. The right to communicate with foreign sovereigns was officially given to Boris by decrees of the Duma of 1588 and 1589. He became a real ruler of the state and, with his characteristic foresight, forced the boy-son to take part in the receptions of ambassadors, etc., as if trying to show in him the heir to his power. Foreign policy during the reign of Boris was distinguished by caution and a predominantly peaceful direction, since Boris, by his nature, did not like risky enterprises, and the country after Grozny needed peace. With Poland, from which heavy defeats were suffered in the previous reign, they tried to maintain peace, albeit through truces, and in 1586, when King Stefan Batory died, an attempt was made, however, unsuccessful, to arrange the election of Tsar Fedor Ioannovich to the Polish kings . With Sweden in 1590, when they were convinced that Poland would not help her, they started a war, and the tsar himself went on a campaign, accompanied by Boris and Fyodor Nikitich Romanov. Thanks to this war, the cities taken by the Swedes under Ivan the Terrible were returned: Yam, Ivan-gorod and Koporye, and in the peace of 1595 Korela, and half of Lapland was received. Active relations were conducted with Austria, which was helped against Poland and the Turks. Relations with the Crimean Tatars were strained due to their frequent raids on the southern outskirts. In the summer of 1591, the Crimean Khan Kazy-Girey, with a horde of one and a half thousand men, approached Moscow itself, but, having failed in small skirmishes with the Moscow troops, retreated, and abandoned the entire convoy; the dear khan suffered heavy losses from the Russian detachments pursuing him. For the reflection of Khan Boris, although it was not he who was the main governor, but Prince F. Mstislavsky, he received the greatest awards of all the participants in the campaign: three cities in the Vazh land and the title of servant, which was considered more honorable than the boyar. The Tatars repaid this unsuccessful campaign in the following 1592 by attacking the Kashirsky, Ryazan and Tula lands, and took away many prisoners. Peace was concluded with the khan in 1594, but relations remained uncertain. With Turkey, the Moscow government tried to maintain as good relations as possible, although it acted contrary to Turkish interests: it supported a party hostile to Turkey in the Crimea, tried to incite the Shah of Persia against Turkey, sent subsidies to the Caesar's court in money and furs for the war against the Turks.

In 1586, the Kakhetian king Alexander, pressed, on the one hand, by the Turks, on the other, by the Persians, surrendered himself under the protection of Russia. He was sent priests, icon painters, firearms and renewed the fortress on the Terek, built under Grozny; they helped against the Tarkovsky ruler, hostile to Alexander, but they did not dare to defend against the Turks. The English, who enjoyed Boris's special favor, were allowed in 1587 to trade in Russia duty-free free trade, but at the same time their request to prohibit other foreigners from trading in Russia was denied. Highly remarkable is the activity of Boris in relation to the outskirts of the Muscovite state as a colonizer and builder of cities. In the land of the Cheremis, pacified at the beginning of Theodore's reign, a number of cities inhabited by Russian people were built to prevent future uprisings: Tsivilsk, Urzhum, Tsarev, a city on Kokshag, Sanchursk, etc. The Lower Volga, where the legs were dangerous, was provided with construction Samara, Saratov and Tsaritsyn, as well as the construction of a stone fortress in Astrakhan in 1589. A city was also built on the remote Yaik (Urals). To protect against the devastating raids of the Crimeans, Boris erected fortresses on the southern steppe outskirts: Kursk (renewed), Livny, Kromy, Voronezh, Belgorod, Oskol, Valuyki, under the cover of which Russian colonization could only go south. How unpleasant these fortifications were for the Tatars can be seen from the letter of the Crimean Khan Kazy-Girey, in which the Khan, pretending to be a well-wisher of the Moscow government, convinces not to build cities in the steppe, since they, being close to the Turkish and Tatar borders, can be attacked all the more easily, both from the Turks and the Tatars. In Siberia, where after the death of Yermak (August 6, 1584) and after the departure of the Cossack squad back to the Urals, the Russian cause seemed lost, the government of Fyodor Ivanovich restored Russian domination. And here, Russian colonization was strengthened by the construction of cities: Tyumen, Tobolsk, Pelym, Berezov, Surgut, Tara, Narym, Ket prison and the transfer of settlers from Russia, mainly northeastern. During the reign of Boris, the fortification of Moscow was also strengthened by the construction of the White City (in 1586), and the stone walls of Smolensk were erected in 1596, which served a great service in the Time of Troubles.

The establishment of the patriarchate (1589) dates back to the reign of Boris, which equalized the primate of the Russian church with the ecumenical eastern patriarchs and gave him primacy over the metropolitan of Kiev. At the same time, 4 archbishoprics were elevated to the dignity of metropolises: Novgorod, Kazan, Rostov and Krutitsy; 6 bishops have become archbishops, and it is proposed to reopen 8 bishoprics. The internal policy of a smart ruler was aimed at establishing order and justice, restoring power and prosperity. The country was already beginning "to console itself greatly from grief and live quietly and serenely." In the mutual struggle of classes, Boris took the side of the small service people. Contemporaries talk about the "annoyances" of his "greatest". This was also manifested in the political sphere - Boris gave way to "thin" businessmen and service people, pushing aside the "noble" ones - and in the economic one. The decrees of 1586 and 1597 on the need to formally strengthen the rights to serfs created a certain barrier to the growth of boyar "yards". The already created consolidation of the peasantry made the landowner's economy more stable and secure, and the decree of 1597 established a 5-year period for claims for fugitives. In 1591, an event took place that had a huge impact on the fate of Boris: on May 15, Tsarevich Dimitri died in Uglich, and the inhabitants of Uglich killed people they suspected of killing the prince. The commission of inquiry found out that the prince, who suffered from epilepsy, while playing at a poke, fell on a knife in a fit and stabbed himself. Popular rumor blamed Boris for the murder. Whether Boris is to blame for the untimely death of the tsarevich remains obscure to this day, but there are already quite a few voices in historiography that do not accuse him. After the Uglich incident, slander more than once blackened Boris, accusing him of various atrocities and often interpreting his best actions in a bad way. Soon after the death of Demetrius (in June of the same 1591), a strong fire broke out in Moscow, which destroyed the entire White City. Boris tried to provide all possible assistance to the victims of the fire, and then a rumor spread that he purposely ordered Moscow to be set on fire in order to attract its inhabitants with favors. The invasion of the Crimean Khan Kazy-Girey near Moscow in the summer of 1591 was also attributed to Boris, who allegedly wanted to divert the attention of the people from the death of Demetrius. They did not spare Boris even from the accusation of the death of Tsar Theodore, even after the death of the groom Xenia, whom he desired, Prince John. Upon the death of Theodore (died January 7, 1598), the last tsar from the Rurik dynasty, everyone swore allegiance to Tsarina Irina in order to avoid an interregnum, but she, alien to lust for power, on the 9th day after the death of her husband retired to the Moscow Novodevichy Convent, where she took her hair under the name of Alexandra. Irina was followed to the monastery by her brother. The administration of the state passes into the hands of the patriarch and the Boyar Duma, and government letters are issued on behalf of Tsarina Irina.

At the head of the government was Patriarch Job, whose actions were guided not only by devotion to Boris, but also by a deep conviction that Boris was the person most worthy to take the throne, and that his election as king would ensure order and tranquility in the state. In favor of the election of Boris, in addition to the property with the late king, his reasonable administration under Theodore spoke most of all, and Theodore's reign was considered by his contemporaries as a happy reign. Moreover, the long-term use of supreme power gave Boris and his relatives enormous resources and linked the interests of the administration of the Muscovite state with his interests. From the very beginning, the patriarch proposes Boris as king and, accompanied by the boyars, the clergy and the people, asks Boris to accept the kingdom, but receives a decisive refusal from him. To break the stubbornness of Boris, a Zemsky Sobor is convened. On February 17, the members of the cathedral gathered to the patriarch in number of over 500; most of them consisted of the clergy, obedient to the patriarch, and service people, supporters of Boris. After Job's speech, which glorified Boris, the Zemsky Sobor unanimously decided "to beat Boris Feodorovich with the forehead and not to look for anyone other than him in the state." On February 21, after many begging, threatened with excommunication, Boris agreed to fulfill the request of the zemstvo people. These repeated refusals on the part of Boris are explained not only by the Russian custom, which required any honor, even a simple treat, not to be accepted at the first invitation, but even more by the desire to strengthen his position by "all-people" election. In the pre-election struggle, supporters of the candidacy of Fyodor Romanov, Bogdan Belsky and even the aged "tsar" Simeon Bekbulatovich were named and found supporters, whose "unwillingness" to the throne was then directly inserted into Boris's cross-kissing record. On April 30, Boris moved from the Novodevichy Convent to the Kremlin and settled with his family in the royal palace. Rumors about the invasion of the Crimeans forced Boris soon (May 2) to leave Moscow at the head of a huge army and stop in Serpukhov, but instead of the horde, envoys from the Khan came with peace proposals. In the camp near Serpukhov, Boris treated the servants with feasts, gave them presents, and they were very pleased with the new tsar; "chahu and henceforth myself from him such a salary." From this campaign the tsar returned triumphantly to Moscow, as if after a great victory. September 1, the day of the new year, Boris was married to the kingdom. During the wedding, under the influence of a joyful feeling, the cautious, restrained Boris broke out the words that struck his contemporaries: “Father, great patriarch Job! God is my witness to this, no one will be poor or poor in my kingdom!". Shaking the collar of his shirt, the king added: "And I will share this last with everyone." The royal wedding, in addition to feasts in the palace, treats of the people, extraordinary favors: service people were given a double annual salary, merchants were given the right to duty-free trade for two years; farmers were exempted from taxes for a year; there is news that it was determined how much the peasants had to work for the landowners and pay them; widows and orphans were given money and food supplies; prisoners in dungeons were released and received assistance; foreigners were released for a year from taxes.

The first years of the reign of Boris were, as it were, a continuation of the reign of Feodor Ivanovich, which is very natural, since power remained in the same hands. Contemporaries praise Boris, saying that "he flourished with splendor, his appearance and mind surpassed all people; a wonderful and sweet-spoken husband, he arranged a lot of meritorious things in the Russian state, hated bribery, tried to eradicate robbery, theft, korchemstvo, but could not eradicate; was light-hearted and merciful and poor-loving!" In 1601, Boris allowed the transfer of peasants throughout Russia, except for the Moscow district, but only from small owners to small ones. As an intelligent man, Boris was aware of the backwardness of the Russian people in education compared with the peoples of Western Europe, he understood the benefits of science for the state. There is news that Boris wanted to start a higher school in Moscow, where foreigners would teach, but met with an obstacle from the clergy. Boris was the first to decide to send several young men to study in Western Europe: in Lübeck, England, France and Austria. This first sending of Russian students abroad was unsuccessful: they all stayed there. Boris sent to Lübeck to invite doctors, miners, cloth workers and various craftsmen to the royal service. The tsar received the Germans from Livonia and Germany who came to Moscow very affectionately, appointed them a good salary and rewarded them with estates with peasants. Foreign merchants enjoyed the patronage of Boris. From foreigners, mainly from Livonian Germans, a special detachment of the royal guard was formed. Under Boris, there were 6 foreign doctors who received huge remuneration. The Germans were allowed to build a Lutheran church in Moscow. There is news that some of the Russians, wanting to imitate foreigners in appearance and thus please the tsar, began to shave their beards. Boris's predilection for foreigners aroused even displeasure in the Russian people. Foreign policy was even more peaceful than under Theodore. From Grozny, Boris inherited the idea of the need to annex Livonia so that, having harbors on the Baltic Sea in his hands, he could enter into communication with the peoples of Western Europe. Open hostility between Poland and Sweden made it possible to realize this dream, if only to act decisively, taking the side of one of the warring states. But Boris tried to join Livonia by diplomatic means and achieved nothing. Imitating Ivan the Terrible, Boris thought of making a vassal kingdom out of Livonia, and for this purpose (in 1599) summoned to Moscow the rival of the sovereigns of Sweden and Poland, the Swedish prince Gustav, the son of the deposed Swedish king Eric XIV, who wandered around Europe as an exile. At the same time, the tsar thought of marrying Gustav to his daughter Xenia, but Gustav, with his frivolous behavior, incurred the wrath of Boris, was deprived of Kaluga, assigned to him before the acquisition of Livonia, and was exiled to Uglich. Boris had a strong desire to intermarry with the European royal houses in the form of exaltation of his own kind. In 1600, A. Vlasyev conducted secret negotiations in Vienna about the marriage of Xenia with Maximilian; Queen Elizabeth of England is trying to find a bride for Theodore. During negotiations with Denmark over the Russian-Norwegian border in Lapland, the tsar's desire to have a Danish prince as his son-in-law was announced. In Denmark, this proposal was readily accepted, and Prince John, brother of King Christian IV, came to Moscow, but soon after his arrival fell dangerously ill and died (in October 1602) to the great grief of Boris and Xenia.

In 1604, negotiations began on the marriage of Xenia with one of the Dukes of Schleswig, but were interrupted by the death of Boris. The tsar was looking for a groom for his daughter and a bride for his son, also among the co-religious owners of Georgia. - Relations with the Crimea were favorable, since the Khan was forced to participate in the Sultan's wars, and, in addition, was constrained by the construction of fortresses in the steppe. In Transcaucasia, Russian policy failed in the clash with the powerful Turks and Persians. Although Shah Abbas was on friendly terms with Boris, he overthrew the Kakhetian king Alexander, allegedly for relations with the Turks, but in fact for relations with Moscow. In Dagestan, the Russians were forced out by the Turks from Tarok and, during the retreat, were cut by the Kumyks; the dominion of Moscow has disappeared in this country. On trade matters, there were relations with the Hanseatic cities: Boris fulfilled the request of 59 cities and gave them letters of commendation for trade; at the same time, the duty was reduced to half for the inhabitants of Lübeck. In Siberia, after the death of Kuchum, Russian colonization continued, and cities were built: Verkhoturye (1598), Mangazeya (1601), Turinsk (1601), Tomsk (1601). Boris had enough intelligence to reach the throne, but no less intelligence, and, perhaps, happiness was needed to stay on the throne. The noble boyars considered themselves humiliated as a result of his accession to the throne, and as they fought against him during the election, they were in opposition afterward and were not averse to intrigues against the hated "worker-tsar". And Boris, a very suspicious person, could not rise to the consciousness that he was an elected zemstvo tsar, whom the will of the people, despite his origin, elevated to the throne, should rise above all accounts with the boyars, especially since he was superior in his personal merits. their. Here is what contemporaries say about the main shortcoming of Boris as a king: “He blossomed like a date, with the leaves of virtue, and if the thorn of envious malice had not darkened the color of his virtue, he could have become like the ancient kings. and therefore he brought upon himself the indignation of the officials of the whole Russian land: from here many insatiable evils rose up against him and his beauty suddenly deposed the flourishing kingdom. This suspicion at first already manifested itself in the oath record, but later it came to disgrace and denunciations. Princes Mstislavsky and V.I. Shuisky, who, due to the nobility of the family, could have claims to the throne, Boris did not allow him to marry. Since 1600, the suspicion of the king has increased markedly.

Perhaps the news of Margeret is not without probability, that at that time dark rumors began that Dimitri was alive. The first victim of Boris' suspicion was Bogdan Belsky, who was commissioned by the tsar to build the city of Boris. According to a denunciation of Belsky's generosity to military people and careless words: "Boris is the tsar in Moscow, and I am in Borisov," Belsky was summoned to Moscow, subjected to various insults and exiled to one of the remote cities. The serf of Prince Shestunov denounced his master. The denunciation was not worthy of attention. Nevertheless, the scammer was told the tsar's word of honor in the square and announced that the tsar, for his service and zeal, would grant him an estate and orders him to serve in the children of the boyars. This encouragement of denunciations had a terrible effect: informers appeared in multitudes. In 1601, the Romanovs and their relatives were denounced. The eldest of the Romanov brothers, Theodore Nikitich, was exiled to the Siya Monastery and tonsured under the name Filaret; his wife, tonsured under the name of Martha, was exiled to the Tolvuisky Zaonezhsky churchyard, and their young son Michael (the future king) was sent to Beloozero. To the despondency produced by disgrace, torture, and intrigues, physical calamities have joined. Since 1601, three years in a row were cropless, and a terrible famine began, so that, as they say, even human meat was eaten. To help the starving, Boris began construction in Moscow and handed out money. This measure caused even greater evil, since the people rushed to Moscow in large masses and died in multitudes from hunger and pestilence in the streets and on the roads. Only the harvest of 1604 ended the famine. Famine and pestilence were followed by robberies. Robber gangs were mainly made up of serfs released by the masters during the famine, as well as from serfs of disgraced boyars. The brave chieftain Khlopok Kosolap appeared near Moscow, but after a stubborn battle he was defeated by the tsarist troops (in 1604). At the beginning of 1604, it became known in Moscow for certain that a man appeared in Lithuania calling himself Tsarevich Dimitri, and in October of the same year the Pretender entered the borders of the Muscovite state, finding adherents everywhere. Although on January 21, 1605 the Pretender was defeated at Dobrynich, he again gathered an army. The matter was in an indecisive position when, on April 13, 1605, Boris ended abruptly, having accepted the schema. Boris's policy deprived him of support among the ruling class - the boyars, aroused hostility towards him from the lower class - the peasants, and service people and free taxpayers have not yet learned to defend their defenders. And after the death of Boris, his family found itself in a tragic situation: without strength, in the face of a formidable enemy. True, Moscow swore allegiance to Boris's son, Theodore, to whom his father tried to give the best possible education, and whom all modern evidence showers with great praise. But the young king, after the shortest reign, died a violent death together with his mother. Princess Xenia, distinguished by her beauty, was spared for the amusement of the impostor; subsequently she cut her hair and died in 1622. The ashes of Tsar Boris, removed under the Pretender from the Archangel Cathedral, under Mikhail Feodorovich were transported to the Trinity-Sergius Lavra, where they rest now; the ashes of the Boris family also rest there.

Russian Biographical Dictionary / www.rulex.ru / 86-volume Encyclopedic Dictionary of Brockhaus and Efron (1890-1907);

New Encyclopedic Dictionary (1910-1916).

Literature. In addition to the general works of the book. Shcherbatov vol. VI, Karamzin X - XI, Artsybyshev book. V, Buturlin "History of the Time of Troubles" vol. I, Solovyov vol. VII and VIII, Kostomarov "The Time of Troubles" vol. I, (separately and in "Monographs") and "Russian history in biographies" vol. I, cf. K.N. Bestuzhev-Ryumin, "Review of events from the death of Tsar Ivan Vasilievich to the election to the throne of Mikhail Fedorovich Romanov" ("Journal of the Ministry of National Education", 1887, July - August); Pavlov, "On the historical significance of the reign of Boris Godunov" (M., 1850, 2nd ed. 1863); S.F. Platonov, "Old Russian legends and stories about the Time of Troubles" (St. Petersburg, 1888); "Letters of K.N. Bestuzhev-Ryumin about the Time of Troubles" (St. Petersburg, 1898); IN. Klyuchevsky, "The Composition of the Representation at Zemstvo Sobors" ("Russian Thought", January books of 1890, 1891, 1892) and "Course of Russian History", parts II and III; DI. Ilovaisky, "History of Russia", volumes III and IV; "Archivum Domus Sapiehanae, ed. Dr. A. Prochaska" (Lvov, 1892); Le P. Pierling, "La Russie et le Saint-siege", II and III (P., 1897 and 1901; III volume recently translated into Russian under the title "Demetrius the Pretender"; M., 1912); S.F. Platonov, "Essays on the History of Troubles in the Moscow State of the 16th-17th Centuries" (St. Petersburg, 1899; 2nd ed. 1901); S.F. Platonov, "Boris Feodorovich Godunov" (in the collection "People of the Time of Troubles", St. Petersburg, 1905); K. Waliszewski, "Les origines de la Russie moderne. La Crise revolutionnaire 1584 - 1614" (P., 1906); there is a Russian translation edited by Shchepkina: "Time of Troubles", (St. Petersburg, 1911); Russian Biographical Dictionary - "Boris Feodorovich (Godunov)", Art. K.N. Bestuzhev-Ryumin and S. P. (in the volume "Betancourt-Buakster"; St. Petersburg, 1908). Sources are named in the indicated works; recently published by G.S. Sheremetev, "Greek Affairs" (in the collection "Sergei Fedorovich Platonov's students, friends and admirers", St. Petersburg, 1911); "Materials on the Time of Troubles in Russia of the 17th century", coll. professor V.N. Aleksandrenko ("Antiquity and Novelty", book XIV, M., 1911); "Journey of His Princely Grace Duke Hans of Schleswig-Holstein to Russia in 1602"; Yu.N. Shcherbachev ("Readings in the Society of History and Antiquities", 1911, book III). P. Lubomirov.

For modern people, the question "Who is Boris Godunov?" will hardly cause difficulty. His name and place in a series of other Russian autocrats are too well known. But the personal assessment of this bright historical character is sometimes ambiguous. Paying tribute to the state mind and the political line that preceded the reforms of Peter I by a hundred years, he is often accused of usurping power and even of infanticide. The personality of Boris Godunov has been the subject of discussion for several centuries now.

Path to power

According to legend, the Godunov family originates from one of the many Tatar princes who settled in Moscow during the time of Ivan Kalita and served the Grand Duke faithfully. The future ruler of Russia himself, Boris Feodorovich Godunov, whose life story is an example of an extraordinary social take-off, was born in 1552 in the family of a small landowner in the Vyazemsky district. If not for a happy coincidence, his name would never have appeared on the pages of national history.

But, as you know, chance loves those who know how to use it. Young and ambitious Boris was just one of those people. He took advantage of the patronage of his uncle, who during the time of Ivan the Terrible became one of the tsar's confidants, and, joining the ranks of the guardsmen, who left a gloomy and bloody mark in history, achieved the favor of the autocrat, making his way into his inner circle. When he became the son-in-law of Malyuta Skuratov, one of the most powerful and most odious representatives of the elite of that era, his position was finally strengthened.

The death of the tsar, which opened new perspectives for Boris

The next step to the pinnacle of power was the marriage of his sister Irina with the heir to the throne, the son of Ivan the Terrible, the weak-willed and weak Tsarevich Fedor. This allowed the small Vyazma landowner to become one of the most powerful people of that time. Historians agree that in the last years of his life, the willful and despotic tsar made most of his decisions under the influence of Godunov.

But the real time of Boris Godunov began after the accession to the throne of his son. Having accepted the royal crown according to the law of succession, Fedor could not govern the country due to mental retardation, and a regency council was created to perform this function. The father-in-law of the young sovereign did not enter it, but through all sorts of intrigues he practically led the state during all fourteen years of his son-in-law's reign.

Works for the benefit of the state

This time was marked by many of his progressive undertakings. Thanks to Godunov, the Russian Orthodox Church became autocephalous. It was headed by Patriarch Job, which increased the country's global prestige. Over the years, the construction of cities and fortresses has been widely developed within the state. A smart and prudent ruler, Godunov invited the most talented architects from abroad, which gave impetus to the development of domestic architecture.

In the capital itself, through his labors, an innovation unheard of at that time was introduced - a water supply system equipped with pumps and connecting the Moscow River with the Stables Yard. In order to protect the city from Tatar invasions, Godunov initiated the construction of a nine-kilometer wall of the White City and a line of fortifications, which were then located on the site of the current Garden Ring. Thanks to them, the capital was saved during a raid in 1591.

Death of a minor heir to the throne

In the same 1591, an event occurred, as a result of which the question of who Boris Godunov is for Russia - a benefactor or a villain, cannot receive an unambiguous answer to this day. The fact is that on May 11, under mysterious and still unclear circumstances, the youngest son of Ivan the Terrible, Tsarevich Dimitri, who was rightfully the heir to the throne, died. Everyone knew that Godunov had long dreamed of the royal throne, and therefore popular rumor declared him the culprit of a grave crime.

The conclusion of the commission of inquiry sent to Uglich, where the tragedy occurred, did not help either. In vain, its chairman, Prince Vasily Shuisky, called the cause of death an accident. This only strengthened the rumors that a conspiracy had been carried out in the palace with the aim of enthroning the usurper and child-killer - the boyar Godunov. Even the successes in foreign policy and the lands returned to him, lost during the Livonian War, did not change the general hostility.

Dream come true

In September 1598 (the biography of Boris Fedorovich Godunov is a direct confirmation of this), the life of this man changes dramatically - after the death of the tsar, the Zemsky Sobor handed him the ancient one. The countdown of the seven-year reign began. From the very first days, the policy of the new sovereign was focused on rapprochement with the West, which gives the right to find common features in it with the reign of the future autocrat Peter I, who carried it out in full.

Like the future reformer of Russia, Godunov tried to involve his subjects in the achievements of world civilization. To this end, he ordered many foreigners to Moscow, who subsequently left a noticeable mark in the history of the country. Among them, along with scientists and architects, were also representatives of trade circles, who became the founders of famous merchant families. The Russian army also benefited from this policy, replenished with many foreign military specialists.

Opposition - covert and overt

But, despite all the good undertakings of the tsar, his political opponents, represented by representatives of the most ancient boyar families, united in opposition and sought to overthrow the sovereign they hated. They secretly and openly tried to counteract all his actions. When in 1601 a severe drought occurred in the country, which lasted three years and claimed the lives of thousands of people, the boyars spread a rumor among the people that it was God's punishment for the blood of the innocently murdered Tsarevich Dimitri.

Trying to counteract his internal enemies, Godunov was forced to resort to repression. Many boyars were executed or sent into exile in those years. But their relatives remained, who hated the king and posed a serious danger to him. They also tried to turn the dark masses against Boris.

The sad end of life and reign

The main misfortune for him was the appearance of False Dmitry, posing as the saved Tsarevich Dimitri. The impostor everywhere spread false information about where he came from and who he was. Boris Godunov did his best to resist him, but his attempts were in vain - the opposition did its job. The people willingly believed the spreading tales and hated him.

The biography of Tsar Boris Fedorovich Godunov contains many mysteries. One of them is the circumstances of his death, which occurred on April 13, 1605. Despite the fact that the health of the sovereign by this time was thoroughly undermined by overwork and nervous stress, there is reason to believe that Boris's death was violent. Some researchers see it as a voluntary departure from life.

Many questions related to this, far from ordinary, historical figure are still waiting to be elucidated. We only superficially know who Boris Godunov is, but what lies in the depths of his multifaceted personality is hidden from our eyes.

Boris Fedorovich Godunov - Russian Tsar (1598-1605).

The clan of the Godunov boyars descended from the Tatar Murza Chet, who left the Horde for Moscow under Ivan Kalita. Boris, who belonged to this family, was born around 1551, entered the court of Ivan the Terrible as one of the guardsmen, in 1570 became the sovereign's squire and soon married Maria, the daughter of the tsar's favorite, Malyuta Skuratov. Terrible fell in love with this dodgy, broad-shouldered handsome man, with black curls and a thick beard, although the new confidant once almost died from the blows of his iron crutch. In 1576, Boris became a kravchim, and in 1580 became a boyar, when the son of the Terrible, Fyodor, married Godunov's sister, Irina.

In the spring of 1584 Ivan IV died. The first persons in power remained not so much representatives of the well-born princes, but rather the “beloved” of Grozny, members of his oprichnina, “shurya”: the brother of his first wife Anastasia, Nikita Romanovich Yuriev, brother of Tsarina Irina Boris Godunov, and his nephew Ivan Fedorovich Mstislavsky. It was they who made up the usual "near thought" or board under the feeble-minded heir to Grozny, Fyodor Ioannovich. Below was another circle - with the youngest son of Ivan IV, the child of Dmitry and his mother, Maria Nagoya. The soul of this circle was Bogdan Belsky. In order to eliminate the rival to Tsar Fedor, Belsky was exiled to Nizhny Novgorod, and Nagikh with Tsarevich Dmitry were sent to Uglich. Nikita Romanovich Yuryev was very old and soon died. Boris gradually took away all the power, with the help of his sister Irina, who submitted to him, who had a great influence on Tsar Fedor. He was hindered only by the heads of the noblest families: Gediminovich - Mstislavsky and Rurikovich Ivan Petrovich Shuisky, a relative of the Yurievs. Mstislavsky was tonsured a monk on a denunciation, and he soon died. But Shuisky managed to arouse hostility in Moscow towards Godunov and attract Metropolitan Dionysius to him. They all decided to demand that the tsar "for the sake of childbearing" divorce the barren Irina and marry the daughter of Mstislavsky. Boris learned about this plan through spies. Shuisky and his comrades were exiled to distant cities, where they soon died. The place of Dionysius was taken by a friend of Godunov, Archbishop Job of Rostov (1587).

Boris has now become the true ruler of the state, with the title of "near great boyar, adviser to the tsar's majesty, equestrian, servant, yard governor, governor of the kingdoms of Kazan and Astrakhan", and, finally, "ruler". He was granted a lot of land and government fees, and even given the right to communicate with foreign sovereigns. Godunov received ambassadors according to the royal rank; and at palace receptions he stood “higher than the rynd” at the throne, and even held a “golden apple of the royal rank”; foreigners called him "blessed majesty" and "Lord Protector of Russia." Next to him, his son Fyodor Borisovich has already begun to officially appear and be mentioned.

The main features of Boris Godunov's policy were already fully determined during this period of his administration of Russia on behalf of Tsar Fyodor. In foreign policy, he did not like to risk war and preferred to settle matters through diplomacy. After the death of Stefan Batory (1586), Boris tried with the help of money to arrange the election of Fyodor Ioannovich to the Polish throne. This attempt failed, but by 1590 Godunov managed to return from the Swedes the cities of Yam, Korela and others taken away by them under Grozny (1590). Boris weakened the Turks with a clever policy. Under the patronage of Moscow surrendered (1586) Kakhetian king Alexander.

Tsar Fyodor Ivanovich. Reconstruction based on Gerasimov's skull

Shakko Photos

As for domestic politics, here Boris Godunov tried in every possible way to win over those social forces that could help him get to power, and to eliminate everything that interfered with the achievement of this goal. From dangerous rivals from among the nobility, he got off with exile. He tried to replace their places with “thin-born” people: according to Avraamy Palitsyn, he robbed “especially the houses and villages of boyars and nobles.” But the middle nobility became the main subject of his concern. Not being able to stop the mass exodus of the peasant population from the landowners' lands of central Russia to the southeastern outskirts, which had only opened up for colonization in the second half of the 16th century, he tried to bring order to this spontaneous process and regulate it with laws. The Godunov government sanctioned the successes made by Russian colonization over the past 30 years on the outskirts and consolidated them by building a number of fortress cities; at the same time, it hindered the further development of colonization, placing the peasant settlers in the position of "fugitives" before the letter of the law and thus paving the way for the final formalization of serfdom. Thus, Boris achieved his immediate goal - providing the state with an army and attracting a class of service people to himself. Wanting to attract the clergy, Boris, contrary to the decisions of the councils, patronized church land ownership; and from 1589 he elevated the head of the Russian church to the rank of patriarch: the Patriarch of Constantinople Jeremiah, who then arrived for alms, consecrated Job as patriarch. For the final strengthening of power for Godunov, in view of the frailty of Fedor, the only thing missing was the elimination of the last offspring of the Rurik family - the young brother of the tsar, Dmitry. In Moscow, rumors began to circulate, recorded by foreigners, that Boris was preparing a violent death for him. Naturally, when on May 15, 1591, Tsarevich Dmitry was killed in Uglich, popular rumor immediately attributed this case to Godunov.

Tsarevich Dmitry. Painting by M. Nesterov, 1899

After the death of Fyodor (1598), Tsarina Irina renounced the throne and took the vows in the Novodevichy Convent. Boris followed her there for the sake of appearances. Godunov's rival could only be the head of the influential Romanov family - Fyodor Nikitich. But only the court nobility could stand for him, and Boris relied on the clergy obedient to Job and on the servants. The hastily convened Zemsky Sobor consisted precisely of these estates: its charter, with almost 500 signatures, elected Godunov. On the Russian New Year, September 1, 1598, Boris was crowned king.

The wife of Fyodor Ioannovich, Tsarina Irina Godunova, sister of Boris

(1551-1605) Russian tsar

Boris Fedorovich Godunov always wanted to have a lot of power and fame. He achieved great power, but the fame of him went so thin that his name still haunts. Much information about him remains in historical documents, and just as much has been written about Tsar Boris in works of art, including such masterpieces of Russian literature as the tragedies of A. Pushkin and A. Tolstoy, as well as numerous stories and novels.

The Godunov clan comes from the Tatar Murza Chet, who began serving in Russia around 1300 under Ivan I Kalita. Boris Godunov belonged to the younger branch of this family. We know almost nothing about his childhood. It is only known that he began to serve under Ivan IV the Terrible. For the first time, his name is mentioned in documents from 1567, where Boris Fedorovich Godunov is named a member of the oprichnina court.

In 1570, Boris Godunov participated in the Serpukhov campaign of Ivan IV, where he served as a rynda, that is, a servant under the royal saadak (bow and arrows). And in the same year he married Maria Skuratova, daughter of the famous tsarist guardsman Malyuta Skuratov. With the help of his father-in-law, in 1578 Godunov got the position of a kravchey. His elevation is also connected with the fact that in 1580 Boris Godunov's sister, Irina, became the wife of Ivan the Terrible's youngest son Fyodor.

After the death of Ivan the Terrible, Boris Godunov becomes the chief adviser to Tsar Fyodor Ioannovich. On the day of Fedor's wedding to the kingdom, Godunov was literally showered with favors: he received the high rank of equerry, and also began to be called his neighbor great boyar and governor of the Kazan and Astrakhan kingdoms.

It must be said that Boris Godunov knew how to use his position, and the fact that the tsar loved his wife Irina greatly helped him advance. Therefore, in a short time, Godunov concentrated enormous power in his hands: he received foreign ambassadors, negotiated and signed treaties. His first concern was to strengthen the borders of the Russian state. In this field, Boris Godunov proved to be a strong and intelligent leader. He resorted to military force only in cases where diplomatic negotiations failed. Under him, the Muscovite state became an important political force not only in Europe but also in Asia. This was facilitated by a reasonable trade policy, in particular, it was Boris Fedorovich Godunov who in 1587 allowed foreign merchants to trade duty-free in Russia.

To facilitate the development of the outlying regions of Russia, Boris Godunov proposed to build Russian cities in the Volga region, as well as along the borders of the steppe regions.

The establishment of the Russian Patriarchate in 1589 also had the most important political consequences. It equated the head of the Russian church with the ecumenical eastern patriarchs, that is, it finally secured the status of the first city of the Russian land for Moscow.

In addition, Boris Godunov proposed limiting the growth of boyar households by enshrining the rights of serfs in the laws and setting a five-year period for searching for fugitive peasants. All these measures were aimed at strengthening the social status of the noble population, allowing the “poor nobles” and service people to rise.

In 1591, Tsarevich Dmitry died under mysterious circumstances. Popular rumor connected his death with the name of Boris Fedorovich Godunov. This formed a dark stain on the biography of Godunov as a statesman, which, however, did not prevent him from taking the royal throne a few years later.

After Boris Godunov became tsar, he showed himself to be a reasonable and at the same time cautious ruler. In 1601, he allowed the annual transfer of peasants to a new owner. As an intelligent and, obviously, well-educated person, Boris Godunov perfectly understood the backwardness of Muscovite Russia. That is why he first decided to send several young men to study in Germany, England and Austria. However, everyone he sent remained abroad. Then Tsar Boris began to invite foreign specialists to Russia - doctors, miners, cloth workers.

Under Boris Fedorovich Godunov, there were six foreign doctors and a fairly large number of other specialists in Moscow, since they were even allowed to build their own Lutheran church and buy houses to live in.

The last years of Boris Godunov's reign were marred by suspicion and envy. The reason was that rumors began to spread in the capital and the state that Tsarevich Dmitry was alive and lay claim to the kingdom. Besides, one misfortune followed another. It seemed that all conceivable and unimaginable troubles fell upon the kingdom of Godunov. Since 1601, a terrible crop failure has swept through Moscow and throughout Russia. This led to epidemics of various diseases, and bands of robbers appeared. And at the beginning of 1604, Polish troops also entered Russian territory, commanded by False Dmitry I.

Despite the fact that on January 21, 1605, Russian troops stopped the detachments of False Dmitry, Tsar Boris felt threatened and felt that this respite would not last long. But he did not have time to do anything, because just three months later he suddenly died. After his death, the inhabitants of Moscow swore allegiance to the son of Boris Theodore. But the young tsar was soon killed during a turmoil skillfully organized by V. Shuisky, and his mother and sisters were tonsured into a monastery.

The ashes of Boris Fedorovich Godunov, first buried in the Archangel Cathedral, were transferred to the Trinity-Sergius Lavra. Thus ended the life of this outstanding man and statesman.

Tsar Boris I Fyodorovich Godunov

According to legend, the Godunovs descended from the Tatar prince Chet, who came to Russia during the time of Ivan Kalita. This legend is recorded in the annals of the beginning of the 17th century. According to the sovereign genealogy of 1555, the Godunovs descended from Dmitry Zern. Godunov's ancestors were boyars at the Moscow court.

Boris Godunov was born in 1552. His father, Fyodor Ivanovich Godunov, nicknamed Krivoy, was a medium-sized Vyazma landowner.

After the death of his father (1569), Boris was taken into his family by his uncle, Dmitry Godunov. During the years of the oprichnina, Vyazma, in which the possessions of Dmitry Godunov were located, passed to the oprichnina possessions. The ignoble Dmitry Godunov was enlisted in the oprichnina corps and soon received the high rank of head of the Bed Order at court.

The promotion of Boris Godunov begins in the 1570s. In 1570 he became a guardsman, and in 1571 he was a friend at the wedding of the tsar with Marfa Sobakina. In the same year, Boris himself married Maria Grigoryevna Skuratova-Belskaya, daughter of Malyuta Skuratov. In 1578, Boris Godunov became a master. Two years after the marriage of his second son Fyodor to Godunov's sister Irina, Ivan the Terrible bestowed the title of boyar on Boris. Godunovs slowly but surely climbed the hierarchical ladder: in the late 1570s - early 1580s. they won several local cases at once, gaining a fairly strong position among the Moscow nobility.

Godunov was smart and cautious, trying to stay in the background for the time being. In the last year of the tsar's life, Boris Godunov gained great influence at court. Together with B.Ya. Belsky, he became one of the close people of Ivan the Terrible. The role of Godunov in the history of the death of the tsar is not entirely clear.

A study of the remains of Ivan the Terrible showed that in the last six years of his life he developed osteophytes, and to such an extent that he could no longer walk - he was carried on a stretcher. Examining the remains of M.M. Gerasimov noted that he had not seen such powerful deposits in the deepest old people. Forced immobility, combined with a general unhealthy lifestyle, nervous shocks, etc., led to the fact that in his 50s, the tsar looked like a decrepit old man.

In August 1582, A. Possevin, in the report of the Venetian Signory, stated that "the Moscow sovereign will not live long." In February and early March 1584, the tsar was still engaged in state affairs. By March 10, the first mention of the disease dates back (when the Lithuanian ambassador was stopped on the way to Moscow "due to the sovereign's illness"). On March 16, deterioration began, the king fell into unconsciousness, but on March 17 and 18 he felt relief from hot baths. But in the afternoon of March 18, the king died. The body of the sovereign was swollen and smelled bad "because of the decomposition of the blood."

Grozny, according to D. Horsey, was "strangled." It is possible that a conspiracy was drawn up against the king. In any case, it was Godunov and Belsky who were next to the tsar in the last minutes of his life, and from the porch they announced to the people about the death of the sovereign.

Vifliofika preserved the Tsar's dying order to Boris Godunov:

“When the Great Sovereign of the last path was honored, the most pure body and blood of the Lord, then as a witness presenting his confessor Archimandrite Theodosius, filling his eyes with tears, saying to Boris Feodorovich: I command you my soul and my son Feodor Ivanovich and my daughter Irina ... ". Also, before his death, according to the chronicles, the tsar bequeathed to his youngest son Dmitry Uglich with all the counties.

Head of government under Tsar Fedor

Fyodor Ioannovich ascended the throne. The new tsar was not able to govern the country and needed a smart adviser, so a regency council of four people was created: Bogdan Belsky, Nikita Romanovich Yuryev (Romanov), princes Ivan Fedorovich Mstislavsky and Ivan Petrovich Shuisky.

On May 31, 1584, on the day of the coronation of the tsar, Boris Godunov was showered with favors: he received the rank of equerry, the title of a close great boyar and governor of the Kazan and Astrakhan kingdoms. However, this did not mean at all that Godunov had sole power - at the court there was a stubborn struggle between the boyar groups of the Godunovs, Romanovs, Shuiskys, and Mstislavskys.

In 1584, B. Belsky was accused of treason and exiled; the following year, Nikita Yuryev died, and the aged Prince Mstislavsky was forcibly tonsured a monk. Subsequently, the hero of the defense of Pskov, I.P., also fell into disgrace. Shuisky.

In fact, since 1585, 13 of the 14 years of the reign of Fyodor Ioannovich, Boris Godunov ruled Russia.

The activities of Godunov's board were aimed at the comprehensive strengthening of statehood. Thanks to his efforts, in 1589 the first Russian patriarch was elected, which he became. The establishment of the patriarchate testified to the increased prestige of Russia. In the domestic policy of the Godunov government, common sense and prudence prevailed. Unprecedented construction of cities and fortifications unfolded.

Boris Godunov patronized talented builders and architects. Church and city construction was carried out on a grand scale. On the initiative of Godunov, the construction of fortresses began in the Wild Field - the steppe outskirts of Russia.

In 1585 the Voronezh fortress was built, in 1586 - Livny.

To ensure the safety of the waterway from Kazan to Astrakhan, cities were built on the Volga - Samara (1586), Tsaritsyn (1589), Saratov (1590).

In 1592 the city of Yelets was restored. On the Donets in 1596 the city of Belgorod was built, to the south in 1600 Tsarev-Borisov was built. The settlement and development of the lands deserted during the yoke to the south of Ryazan (the territory of the present Lipetsk region) began. The city of Tomsk was founded in Siberia in 1604.

In the period from 1596 to 1602, one of the most grandiose architectural structures of pre-Petrine Russia was built - the Smolensk fortress wall, which later became known as the "stone necklace of the Russian Land." The fortress was built on the initiative of Godunov to protect the western borders of Russia from Poland.

A. Kivshenko. "Tsar Fyodor Ivanovich puts a golden chain on Boris Godunov"

Under him, unheard of innovations entered the life of Moscow, for example, a water pipe was built in the Kremlin, through which water rose with powerful pumps from the Moscow River through the dungeon to the Konyushenny yard. New fortifications were also built. In 1584-1591. under the guidance of the architect Fyodor Savelyev, nicknamed the Horse, the walls of the White City were erected with a length of 9 km. (they encircled the area enclosed within the modern Boulevard Ring). The walls and 29 towers of the White City were made of limestone, lined with bricks and plastered. In 1592, on the site of the modern Garden Ring, another line of fortifications was built, a wooden and earthen one, nicknamed the “Skorodom” for the speed of construction.

In the summer of 1591, the Crimean Khan Kazy-Girey with a 150,000-strong army approached Moscow, however, being at the walls of a new powerful fortress and under the guns of numerous guns, he did not dare to storm it. In small skirmishes with the Russians, the Khan's detachments were constantly defeated; this forced him to retreat, abandoning the convoy. On the way to the south, to the Crimean steppes, the Khan's army suffered heavy losses from the Russian regiments pursuing him. For the victory over Kazy-Girey, Boris Godunov received the greatest reward of all the participants in this campaign (although it was not he who was the main governor, but Prince Fyodor Mstislavsky): three cities in the Vazh land and the title of servant, which was considered more honorable than the boyar.

Godunov sought to alleviate the situation of the townspeople. By his decision, merchants and artisans who lived in "white" settlements (privately owned, paying taxes to large feudal lords) were included in the population of "black" settlements (paying tax - "tax" - to the state). At the same time, the size of the “tax” levied on the settlement as a whole was left the same, and the share of an individual citizen in it decreased.

The economic crisis of the 1570s - early. 1580s forced to go to the establishment of serfdom. On November 24, 1597, a decree was issued on “lesson years”, according to which peasants who had fled from their masters “until this year in five years” were subject to investigation, trial and return “back to where someone lived.” The decree did not apply to those who fled six years ago and earlier, they were not returned to their former owners.

Nicholas Ge. Boris Godunov and Tsarina Marfa, summoned to Moscow for interrogation about Tsarevich Dmitry at the news of the appearance of an impostor

In foreign policy, Godunov proved himself to be a talented diplomat. On May 18, 1595, a peace treaty was concluded in Tyavzin (near Ivangorod), which ended the Russian-Swedish war of 1590-1593. Godunov managed to take advantage of the difficult internal political situation in Sweden, and Russia, according to the agreement, received Ivangorod, Yam, Koporye and Korela. Thus, Russia regained all the lands transferred to Sweden following the unsuccessful Livonian War.

Death of Tsarevich Dmitry

The heir to the throne during the life of Tsar Fedor was his younger brother Dmitry, the son of the seventh wife of Ivan the Terrible. On May 15, 1591, the prince died under unclear circumstances in the specific city of Uglich. The official investigation was conducted by the boyar Vasily Shuisky. Trying to please Godunov, he reduced the causes of what happened to Nagikh's "negligence", as a result of which Dmitry accidentally stabbed himself with a knife while playing with his peers. The prince, according to rumors, was sick with an "epilepsy" disease (epilepsy).

The chronicle of the times of the Romanovs blames Boris Godunov for the murder, because Dmitry was the direct heir to the throne and prevented Boris from advancing to him. Isaac Massa also writes that "I am firmly convinced that Boris hastened his death with the assistance and at the request of his wife, who wanted to become queen as soon as possible, and many Muscovites shared my opinion." Nevertheless, Godunov's participation in the conspiracy to kill the tsarevich has not been proven.

In 1829, the historian M.P. Pogodin was the first to take the risk of defending Boris's innocence. The original of the criminal case of the Shuisky Commission, discovered in the archives, became the decisive argument in the dispute. He convinced many historians of the 20th century (S.F. Platonov, R.G. Skrynnikov) that the true cause of the death of Ivan the Terrible's son was still an accident.

Godunov on the throne

On January 7, 1598, Fyodor Ioannovich died, and the male line of the Moscow branch of the Rurik dynasty was cut short. The only close heir to the throne was the second cousin of the deceased, Maria Staritskaya (1560-1611).

Boris Godunov is informed of his election to the kingdom

After attempts to appoint the widow of the deceased Tsar Irina, Boris's sister, as the ruling queen, on February 17 (27), 1598, the Zemsky Sobor (including Irina's "recommendation") elected Fyodor's brother-in-law Boris Godunov as king and swore allegiance to him.

On September 1 (11), 1598, Boris was married to the kingdom. A close property, which was typical for that time, outweighed the distant relationship of possible contenders for the throne. No less important was the fact that Godunov had long actually ruled the country on behalf of Fedor, and was not going to let go of power after his death.

The reign of Boris was marked by the beginning of Russia's rapprochement with the West. Before there was no sovereign in Russia who would have been so kind to foreigners as Godunov. He began to invite foreigners to serve. In 1604 he sent okolnichiy M.I. Tatishchev to Georgia to marry his daughter to the local prince.

Repression

The first tsar not from Rurikovich (except for such figurehead as Simeon Bekbulatovich), Godunov could not help but feel the precariousness of his position. In his suspiciousness, he was a little inferior to Grozny. Having ascended the throne, he began to settle personal scores with the boyars. According to a contemporary, “he blossomed, like a date, with leaves of virtue, and if the thorn of envious malice had not darkened the color of his virtue, he could have become like the ancient kings. From slanderers, he vainly accepted the slander of the innocent in a rage, and therefore brought the indignation of the officials of the entire Russian land: from here many insatiable evils rose up against him and his beauty suddenly deposed the flourishing kingdom.

At first, this suspicion was already manifested in the oath record, but later it came to disgrace and denunciations. Princes Mstislavsky and V.I. Shuisky, who, due to the nobility of the family, could have claims to the throne, Boris did not allow him to marry. Since 1600, the suspicion of the king has increased markedly. Perhaps the news of Margeret is not without probability that already at that time dark rumors had spread that Dimitri was alive. The first victim of Boris' suspicion was Bogdan Belsky, who was commissioned by the tsar to build Tsarev-Borisov. According to a denunciation of Belsky’s generosity to military people and careless words: “Boris is the tsar in Moscow, and I am in Borisov,” Belsky was summoned to Moscow, subjected to various insults and exiled to one of the remote cities.

The serf of Prince Shestunov denounced his master. The denunciation was not worthy of attention. Nevertheless, the scammer was told the tsar's word of honor in the square and announced that the tsar, for his service and zeal, would grant him an estate and orders him to serve in the children of the boyars. In 1601, the Romanovs and their relatives suffered under a false denunciation. The eldest of the Romanov brothers, Theodore Nikitich, was exiled to the Siya Monastery and tonsured under the name Filaret; his wife, tonsured under the name of Martha, was exiled to the Tolvuisky Zaonezhsky churchyard, and their young son Michael (the future king) to Beloozero. Godunov's persecution aroused sympathy among the people for his victims. So the peasants of the Tolvui churchyard secretly helped the nun Martha and "visited" for her the news about Filaret.

Great Famine

The reign of Boris began successfully, but a series of disgrace gave rise to despondency, and soon a real disaster broke out. In 1601, there were long rains, and then early frosts broke out and, according to a contemporary, “beat the strong scum of all the work of human deeds in the fields.” The next year, the crop failure was repeated. A famine began in the country, which lasted three years. The price of bread has increased 100 times. Boris forbade selling bread more than a certain limit, even resorting to the persecution of those who inflated prices, but he did not achieve success. In an effort to help the starving, he spared no expense, widely distributing money to the poor. But bread became more expensive, and money lost its value. Boris ordered the royal barns to be opened for the starving. However, even their supplies were not enough for all the hungry, especially since, having learned about the distribution, people from all over the country reached out to Moscow, leaving the meager supplies that they still had at home. About 127 thousand people who died of starvation were buried in Moscow, and not everyone had time to bury them. There were cases of cannibalism. People began to think that this was God's punishment. There was a conviction that the reign of Boris is not blessed by God, because it is lawless, achieved by untruth. Therefore, it cannot end well.

Cathedral Square in the time of Godunov

In 1601-1602. Godunov even went to the temporary restoration of St. George's Day. True, he did not allow the exit, but only the export of the peasants. The nobles thus saved their estates from final desolation and ruin. The permission given by the Godunovs concerned only small service people, it did not extend to the lands of members of the Boyar Duma and the clergy. But this step did not greatly increase the popularity of the king.

Mass starvation and dissatisfaction with the establishment of "lesson years" caused a major uprising led by Khlopok (1602-1603), in which peasants, serfs and Cossacks took part. The insurrectionary movement covered about 20 districts of central Russia and the south of the country. The rebels united in large detachments that advanced towards Moscow. Boris Godunov sent an army against them under the command of I.F. Basmanov.

In September 1603, in a fierce battle near Moscow, the rebel army of Khlopok was defeated. Basmanov died in battle, and Khlopok himself was seriously wounded, captured and executed.

At the same time, Isaac Massa reports that “... there were more grain reserves in the country than all the inhabitants could eat it in four years ... noble gentlemen, as well as in all monasteries and many rich people, barns were full of bread, some of it was already rotted from years of lying, and they didn't want to sell it; and by the will of God the king was so blinded, despite the fact that he could order whatever he wanted, he did not command in the strictest way that everyone should sell their bread.

Appearance of an impostor

Rumors began to circulate throughout the country that the "born sovereign", Tsarevich Dmitry, was alive. Detractors spoke unflatteringly about Godunov - "worker". At the beginning of 1604, a letter from a foreigner from Narva was intercepted, in which it was announced that Dmitry, who had miraculously escaped, was with the Cossacks, and great misfortunes would soon befall the Moscow land.

October 16, 1604 False Dmitry I with detachments of Poles and Cossacks moved to Moscow. Even the curses of the Moscow Patriarch did not cool the enthusiasm of the people on the path of "Tsarevich Dmitry". However, in January 1605, in the battle of Dobrynich, government troops defeated the impostor, who, with the few remnants of his army, was forced to leave for Putivl.

Death and offspring

Tomb of the Godunovs in the Trinity-Sergius Lavra

The situation for Godunov was complicated due to his state of health. As early as 1599, there are references to his illnesses, and the king was often unwell in the 1600s. April 13, 1605 Boris Godunov seemed cheerful and healthy, he ate a lot and with appetite. Then he climbed the tower, from which he often surveyed Moscow. Soon he came down from there, saying that he felt faint. They called the doctor, but the king felt worse: blood began to flow from his ears and nose. The king lost his senses and soon died. There were rumors that Godunov poisoned himself in a fit of despair. According to another version, he was poisoned by his political opponents; the version of natural death is more likely, since Godunov had often been ill before. He was buried in the Kremlin Archangel Cathedral.

The son of Boris, Fyodor, became king, an educated and extremely intelligent young man. Soon there was a rebellion in Moscow, provoked by False Dmitry. Tsar Fedor and his mother were killed, leaving only Boris's daughter Xenia alive. The bleak fate of the impostor's concubine awaited her. It was officially announced that Tsar Fyodor and his mother were poisoned. Their bodies were exposed. Then Boris's coffin was taken out of the Archangel Cathedral and reburied in the Varsonofevsky Monastery near Lubyanka. His family was also buried there: without a funeral service, like suicides.

Under Tsar Vasily Shuisky, the remains of Boris, his wife and son were transferred to the Trinity Monastery and buried in a sitting position at the northwestern corner of the Assumption Cathedral. In the same place in 1622 Xenia was buried, in monasticism Olga.

In 1782, a tomb was built over their tombs.

In culture

Fyodor Chaliapin as Boris Godunov

In 1710, the German composer Johann Mattheson wrote the opera Boris Godunov, or the Throne Reached by Cunning. However, the premiere of the opera took place only in June 2007 - for a long time the score was kept in the Hamburg archive, then in Yerevan, where it ended up after the Great Patriotic War.

In 1824-1825. Pushkin wrote the tragedy "Boris Godunov" (published in 1831), dedicated to the reign of Boris Godunov and his conflict with False Dmitry I. The tragedy takes place in 1598-1605. and ends with a description of the murder of Fedor and the “proclamation” of “Dmitry Ivanovich” as the new tsar (the final remark of the tragedy was widely known - the people are silent). The first production of the tragedy - 1870, the Mariinsky Theater in St. Petersburg.

In 1869, Modest Mussorgsky finished work on the opera of the same name based on the text of Pushkin's drama, which was first staged at the same Mariinsky Theater (1874).

In 1870 A.K. Tolstoy published the tragedy "Tsar Boris", the action of which, like that of Pushkin, covers the seven years of the reign of Boris Godunov; the tragedy is the final part of the historical trilogy (the first - "The Death of Ivan the Terrible" and "Tsar Fyodor Ioannovich"). Witzraor change.

False Dmitry I. June 1 (11), 1605 - May 17 (27), 1606 - Tsar and Grand Duke of All Russia, Autocrat.

Copyright © 2015 Unconditional Love