Nikolay Kostomarov

(born in 1817 - d. in 1885)

A classic of Ukrainian historiography. One of the founders of the Cyril and Methodius Society.

Nikolai Ivanovich Kostomarov occupies a very special place among Russian and Ukrainian historians. This man was in love with history, he probably treated it not even as a science, but as an art. Nikolai Ivanovich did not perceive the past with detachment, from the outside. Perhaps experts will say that this is not the best trait for a scientist. But it was his enthusiasm, love, passion, imagination that made Kostomarov such an attractive figure for compatriots. It is thanks to his caring, his subjective attitude to history that she aroused the interest of Russians and Ukrainians. The merit of Nikolai Ivanovich before the Russian, and especially the Ukrainian historical science is exceptionally great. Unlike many of his contemporaries, Kostomarov insisted on the independent significance of Ukrainian history, language and culture. He infected many people with his love for the heroic and romantic past of Little Russia, its people, its traditions. Vasily Klyuchevsky wrote about his colleague as follows: "Everything that was dramatic in our history, especially in the history of our southwestern outskirts, all of this was told by Kostomarov, and told with the direct skill of a storyteller who experiences deep pleasure from his own story."

Nikolai Ivanovich Kostomarov did not absorb any special love for Little Russia from childhood, although his mother was a Ukrainian, the child was brought up in the mainstream of Russian culture. Nikolay was born on May 4 (16), 1817 in the village of Yurasovka (now Olkhovatsky district of the Voronezh region). His father, a retired captain Ivan Petrovich Kostomarov, was a landowner. At one time he liked one of the serf girls - Tatyana Petrovna. Ivan sent her to study in St. Petersburg, and upon his return he married her. The marriage was officially registered after Kolya's birth, and the father never had time to adopt the boy.

Nikolai's father was an educated man, he especially admired the French enlighteners, but at the same time he was cruel to his servants. The fate of Ivan Kostomarov was tragic. The mutinous peasants killed the master and robbed his house. This happened when Nikolai was 11 years old. So Tatyana Petrovna took care of him. Nikolai was sent to the Voronezh boarding school, then transferred to the Voronezh gymnasium. Biographers disagree as to why the future historian could not sit still. Apparently, he was expelled for pranks. But he behaved badly, in particular, because his abilities required a more serious level of teaching. In the Moscow boarding house, where Kostomarov was for some time during his father's life, the talented boy was christened enfant miraculeux(magic child).

At the age of 16, Nikolai Kostomarov went to the university closest to his native places - Kharkov. He entered the Faculty of History and Philology. At first, Kostomarov studied neither shaky nor shaky. The teachers did not make a big impression on him, he rushed from topic to topic, studied antiquity, improved languages, studied Italian. Then he became close friends with two teachers, whose influence determined his fate. One of them was Izmail Sreznevsky, described in this book, a pioneer of Ukrainian ethnography, publisher of the romantic "Zaporizhzhya Starina". Kostomarov spoke with enthusiasm about the work of this scientist, he himself was infected with love for Little Russian culture. He was also influenced by his personal acquaintance with other luminaries of the new Ukrainian culture - Kvitka, Metlinsky.

M. Lunin had a great influence on Kostomarov, who began teaching history to Nikolai and his classmates in the third year. After a while, Nikolai Ivanovich had already completely decided on his scientific predilections, he fell in love with history.

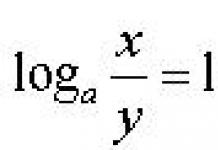

The credo of Kostomarov as a historian is being formed. He asked himself a landmark question for himself and for all Russian historiography:

“Why is it that in all stories they talk about outstanding statesmen, sometimes about laws and institutions, but they seem to neglect the life of the masses? Poor peasant, farmer, toiler, as if it does not exist for history. "

The idea of the history of the people and their spiritual life, in contrast to the history of the state, became the main idea of Kostomarov. In close connection with this idea, the scientist proposes a new approach to studying the past:

“Soon I came to the conviction that history should be studied not only from dead chronicles and notes, but also from living people. It cannot be that centuries of past life are not imprinted in the life and memories of descendants; you just need to start looking, and surely there will be much that has been missed by science until now. But where do you start? Of course, with the study of my Russian people, and since I then lived in Little Russia, then start with the Little Russian branch. "

The scientist begins his own not only archival, but primarily ethnographic research - he walks through the villages, writes down legends, studies the language and customs of the Ukrainians. (Not without incidents. On one of the "Vechornitsa", where a young student was scurrying about with a notebook, he was almost beaten by local guys.) Gradually, the romantically inclined young man is captured by pictures of the heroic past - the Cossacks, the struggle against Poles and Tatars. The historian was especially attracted by the social structure of the Sich in the Zaporozhye period of Ukrainian history. Kostomarov already stood on rather strong democratic-republican positions, so that the election of power, its responsibility before the common people could not but impress Nikolai Ivanovich. This is how his somewhat enthusiastic attitude towards the Ukrainian people as a bearer of democratic ideals is formed.

In 1836, Kostomarov passed his final exams with excellent marks, went home and there he found out that he was deprived of his Ph.D. degree for the fact that he had a “good” grade in theology in his first year - he had to retake this and some other subjects. At the end of 1837, Nikolai Ivanovich still received his candidate's certificate.

The biography of Nikolai Kostomarov is replete with unexpected twists of fate, some kind of uncertainty of the scientist's aspirations. So, for example, after graduating from university, he decided to enlist in the army, for some time he was a cadet in the Kinburn Dragoon Regiment. There, the authorities very quickly found out that the newcomer was categorically not suitable for military service - much more than fulfilling his direct duties, Nikolai Ivanovich was interested in the rich local archive in Ostrogozhsk, he wrote a study on the history of the Ostrogozh Cossack regiment, dreamed of compiling the “History of Sloboda Ukraine”. He served less than a year, his superiors in a friendly way advised him to leave the military career ...

In the spring of 1838, Kostomarov spent in Moscow, where he listened to Shevyrev's lectures. They further supported the romantic mood in him in relation to the common people. Nikolai Ivanovich began to write literary works in Ukrainian, using the pseudonyms Jeremiah Galka and Ivan Bogucharov. In 1838 he published his drama "Sava Chaly", in 1839 and 1840 - poetic collections "Ukrainian ballads" and "Vetka"; in 1841 - the drama Pereyaslavska Nich. Heroes of Kostomarov - Cossacks, Haidamaks; one of the most important topics is the fight against the Polish oppressors. Some of the works were based on Ukrainian legends and folk songs.

In 1841, Nikolai Ivanovich submitted to the faculty his master's thesis "On the causes and nature of the union in Western Russia" (it was about the Brest church union in 1596). A year later, this work was accepted for defense, but it did not bring Kostomarov a new degree. The fact is that the church and censorship spoke out categorically against such a study, and ultimately the Minister of Education Uvarov personally ordered the destruction of all copies of Kostomarov's first dissertation. The work described too many facts concerning the immorality of the clergy, heavy extortions from the population, uprisings of the Cossacks and peasants. The historian had to turn to a neutral topic. The dissertation "On the Historical Significance of Russian Folk Poetry" did not cause such a sharp reaction, and in 1844 Kostomarov successfully became a master of historical sciences. This was the first ethnographic dissertation in Ukraine.

Already in Kharkov, a circle of young Little Russians gathers around the young historian (Korsun, Korenitsky, Betsky and others), who dream of the revival of Little Russian literature, talk a lot about the fate of the Slavic world, the peculiarities of the national history of Ukraine. The life and work of Bohdan Khmelnitsky becomes the topic of the next scientific research of Kostomarov. In particular, in order to visit the places where the events associated with this powerful figure of Ukrainian history took place, Nikolai Ivanovich is assigned as a teacher to the Rivne gymnasium. Then, in 1845, he went to work in one of the Kiev grammar schools.

The following year, Kostomarov became a teacher of Russian history at Kiev University, his lectures invariably arouse great interest. He read not only history, but also Slavic mythology. As in Kharkov, a circle of progressively minded Ukrainian intellectuals gathers in a new place, cherishing the dream of developing an original Ukrainian culture, combining these national aspirations with some political ones - the liberation of the people from serfdom, national, religious oppression; a change in the system towards the republican one, the creation of a pan-Slavic federation, in which Ukraine will be assigned one of the first places. The circle was named "Cyril and Methodius Society". Kostomarov played one of the first violins in it. Nikolay Ivanovich is the main author of the programmatic work of the society - "The Book of the Life of the Ukrainian People". Other members include P. Kulish, A. Markevich, N. Gulak, V. Belozersky, T. Shevchenko. If the latter adhered to rather radical views, then Kostomarov is usually called a moderate, liberal Cyril-Methodian, he emphasized the need for a peaceful way of transforming the state and society. With age, his demands became even less radical, limited to educational ideas.

On the denunciation of student Petrov, the "Cyril and Methodius Society" was defeated in 1847. Naturally, there could be no talk of any continuation of the historian's work at the university. Kostomarov was sent to the Peter and Paul Fortress. There he served a year, after which he was sent to administrative exile in Saratov, where he lived until 1852. In Kiev, Kostomarov left his bride - Alina Kragelskaya. She was a graduate of Mrs. De Melyan's boarding school, where Nikolai Ivanovich taught for some time. Kragelskaya was a talented pianist; she was invited to the Vienna Conservatory by Franz Liszt himself. Despite the protests of her parents, who believed that Kostomarov was no match for her, Alina firmly decided to marry a historian. He rented a wooden mansion near the famous St. Andrew's Church. It was there that the police took him on March 29, 1847, on the eve of the wedding. (By the way, Taras Grigorievich Shevchenko also found himself in Kiev at that moment precisely about the upcoming wedding of his friend, Kostomarov.)

In Saratov, Kostomarov worked in the criminal department and the statistical committee. He made a close acquaintance with Pypin and Chernyshevsky. At the same time, he did not stop working on the composition of historical works, although there was a ban on their publication, which was lifted only in the second half of the 50s.

The attitude of NI Kostomarov to the tasks of the historian, to the methods of his work is curious. On the one hand, Nikolai Ivanovich emphasized that the works should be aimed at "strict, inexorable truth" and not indulge "the old prejudices of national arrogance." On the other hand, Kostomarov, like very few others, is accused of insufficient knowledge of factual material. No, of course, he worked a lot in the archives, had an amazing memory. But too often he relied only on memory, which is why he made numerous inaccuracies and simple mistakes. Moreover, with regard to comments made to him about the free handling of sources and the composing of history, it was in this that the scientist saw the vocation of the historian, for "composing" history, according to his concept, means "comprehending" the meaning of events, giving them a reasonable connection and a harmonious form not limited to rewriting documents. Here is Kostomarov's typical reasoning: “If we had not received any news that the Pereyaslavskaya Rada read the conditions under which Little Russia began to unite with the Moscow state, then I would have been convinced that they were read there. How could it be otherwise? " Such ideas are not always supported by serious historians, but Kostomarov, using "common sense", built a coherent picture of what happened, and is it not for this reason that his historical works are always colorful, interesting, captivating the reader, which, in fact, serves to popularize historical knowledge, pushes further development science (since it arouses the curiosity of the reading public).

It has already been said that Nikolai Kostomarov paid special attention to folk history as opposed to the military-administrative direction in this science. He was looking for that "end-to-end idea" that connects the past, present and future, gives events a "reasonable connection and a slender look." Kostomarov delved deeper into the historical being of a person, sometimes doing it irrationally, trying to understand the mentality of the people. The "spirit of the people" was conceived by these scientists as the real fundamental principle of the historical process, the deep meaning of the life of the people. All this led to the fact that some researchers reproach Nikolai Ivanovich with a certain mysticism.

The main idea of Kostomarov about the Ukrainian people is to emphasize its differences from the Russian people. The historian believed that democracy is inherent in the Ukrainian people, it retains and gravitates towards the specific-veche principle, which in the course of history was defeated in Russia by the beginning of "autocracy", the expression of which is the Russian people. Kostomarov himself, naturally, is more sympathetic to the specific veche structure. He sees its continuation in the Cossack republic, the period of the hetmanate in Ukraine seems to him the brightest, most majestic in the history of Ukraine. At the same time, Nikolai Kostomarov is extremely negative about Moscow's constant striving to unite and subjugate vast territories and masses of people to the will of one person, describing such figures as Ivan the Terrible, in the darkest tones, condemns the actions of Catherine the Great to liquidate the Zaporozhye freemen. In addition to Southwestern Russia, which has long preserved the tradition of federation, another ideal of Kostomarov is the veche republics of Novgorod and Pskov.

Obviously overestimating the political influence of the people in both cities, Nikolai Ivanovich deduces the history of these political formations from South-Western Russia. Allegedly, immigrants from the south of Russia introduced their democratic orders in the northern merchant republics - a theory that is in no way confirmed by modern data from the history and archeology of Novgorod and Pskov. Kostomarov expounded his views on this matter in detail in the works "Novgorod", "Pskov", "North Russian People's Governments".

In Saratov, Kostomarov continued to write his "Bogdan Khmelnitsky", began a new work on the inner life of the Moscow state of the 16th-17th centuries, made ethnographic excursions, collected songs and legends, got acquainted with schismatics and sectarians, wrote the history of the Saratov region (local history is one of the historians Wherever he was - in Kharkov, on the Volyn, on the Volga - he always carefully studied the history and customs of the local population). In 1855, the scientist was allowed a vacation to St. Petersburg, which he used to finish his work on Khmelnitsky. In 1856, the ban on the publication of his writings was lifted and police supervision was removed from him. Having made a trip abroad, Kostomarov again settled in Saratov, where he wrote "The Riot of Stenka Razin" and took part as a clerk of the provincial committee for improving the life of the peasants, in the preparation of the peasant reform. In the spring of 1859 he was invited by St. Petersburg University to the department of Russian history. The ban on teaching activity was lifted at the request of Minister E.P. Kovalevsky, and in November 1859 Kostomarov began lecturing at the university. This was the time of the most intense work in the life of Kostomarov and his greatest popularity.

Nikolai Kostomarov's lectures (the course was called "History of Southern, Western, Northern and Eastern Russia in the specific period"), as always, were perfectly received by progressive-minded youth. He characterized the history of the Moscow state in pre-Petrine times much more sharply than his colleagues, which objectively contributed to greater truthfulness in his assessments. Kostomarov, in full accordance with his scientific credo, presented history in the form of the life of ordinary people, the history of moods, aspirations, the culture of individual peoples of the vast Russian state, paying special attention to Little Russia. Soon after starting work at the university, Nikolai Ivanovich was elected a member of the archaeographic commission, edited the multivolume edition of Acts Relating to the History of Southern and Western Russia. He used the found documents when writing new monographs, with the help of which he wanted to give a new complete history of Ukraine from the time of Khmelnytsky. Fragments of Kostomarov's lectures and his historical articles constantly appeared in Russkoye Slovo and Sovremennik. Since 1865, together with M. Stasyulevich, he published the literary-historical journal Vestnik Evropy.

Kostomarov became one of the organizers and authors of the Ukrainian magazine Osnova, founded in St. Petersburg. In the journal, the works of the historian occupied one of the central places. In them, Nikolai Ivanovich defended the independent significance of the Little Russian tribe, polemicized with Polish and Russian authors who denied it. He even spoke personally with Minister Valuev after the latter issued his famous circular banning the publication of books in Ukrainian. It was not possible to convince the high-ranking dignitary of the need to soften the rules. However, Kostomarov had already lost a significant share of his former radicalism, economic issues - so interesting to other democrats - worried him extremely weakly. In general, to the displeasure of the revolutionaries, he argued that the Ukrainian people were “classless” and “bourgeois”. Kostomarov reacted negatively to any harsh protests.

In 1861, due to student riots, St. Petersburg University was temporarily closed. Several professors, including Kostomarov, organized the reading of public lectures at the City Duma (Free University). After one of these lectures, Professor Pavlov was expelled from the capital, and in protest, many colleagues decided not to go to the department. But Nikolai Ivanovich was not among these “Protestants”. He did not join the action and on March 8, 1862 tried to give another lecture. The audience booed him, and the lecture never began. Kostomarov left the faculty of St. Petersburg University. Over the next seven years, he was invited twice by Kiev and once by Kharkov universities, but Nikolai Ivanovich refused - according to some sources, on the direct instructions of the Ministry of Public Education. He had to completely go into archival and writing activities.

In the 60s from the pen of the historian came out such works as "Thoughts on the federal principle in Ancient Rus", "Traits of South Russian folk history", "Battle of Kulikovo", "Ukraine". In 1866, “The Time of Troubles of the Moscow State” appeared in the “Vestnik Evropy”; later, “The Last Years of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth” was published there. In the early 70s, Kostomarov began work “On the Historical Significance of Russian Song Folk Art”. Caused by a weakening of vision, a break in archival studies in 1872 was used by Kostomarov to compile "Russian history in the biographies of its main figures." This is one of the most important works of the historian. Three volumes contain vivid biographies of princes, tsars, advisers, metropolitans, of course, hetmans, but also popular leaders - Minin, Razin, Matvey Bashkin.

In 1875, Kostomarov suffered a serious illness, which, in fact, did not leave him until the end of his life. And in the same year he married the same Alina Kragelskaya, whom he parted with like Edmond Dantes many years ago. By this time, Alina already bore the surname Kisel, had three children from her late husband, Mark Kisel.

The historian continued to write fiction, including on historical themes - the novel "Kudeyar", the stories "Son", "Chernigovka", "Kholui". In 1880, Kostomarov wrote an amazing essay "Animal Riot", which, not only in name, but also in subject matter, preceded Orwell's famous dystopia. The essay condemned the revolutionary programs of the People's Will in allegorical form.

Kostomarov's views on history in general and the history of Little Russia in particular changed somewhat at the end of his life. Increasingly, he dryly recounted the facts he found. Probably, he became somewhat disillusioned with the heroes of Ukraine's past. (And at one time he even called the so-called Ruin a heroic period.) Although, perhaps, the historian is simply tired of struggling with the official point of view. But in the work "Ukrainofilstvo", published in "Russkaya Starina" in 1881, Kostomarov continued to defend the Ukrainian language and literature with the same conviction. At the same time, the historian in every possible way disowned the ideas of political separatism.

This text is an introductory fragment. From the book of 100 great Ukrainians the author Team of authorsNikolai Kostomarov (1817-1885) historian, romantic poet, social thinker, public figure Along with the greatest scientists of the middle of the 19th century N. Karamzin, S. Soloviev, V. Klyuchevsky, M. Grushevsky is Nikolai Ivanovich Kostomarov, an unsurpassed historian and

From the book Encyclopedic Dictionary (N-O) author Brockhaus F.A.Novikov Nikolai Ivanovich Novikov (Nikolai Ivanovich) - a famous public figure of the last century, born. Apr 26. 1744 in the village of Avdotino (Bronnitsky district, Moscow province) in the family of a sufficient landowner, he studied for several years in Moscow at the university gymnasium, but in 1760

TSB From the book Great Soviet Encyclopedia (KR) of the author TSB TSB From the book Great Soviet Encyclopedia (HA) of the author TSB From the book Great Soviet Encyclopedia (SU) of the author TSBSus Nikolai Ivanovich Sus Nikolai Ivanovich, Soviet scientist, specialist in the field of agroforestry, Honored Scientist of the RSFSR (1947), honorary member of VASKhNIL (since 1956). Graduated from the Forestry Institute in St. Petersburg

From the book Great Soviet Encyclopedia (LU) of the author TSB From the book Great Soviet Encyclopedia (ZI) of the author TSB From the book Great Soviet Encyclopedia (HI) of the author TSB From the book of 100 famous Kharkiv citizens the author Karnatsevich Vladislav LeonidovichNikolay Ivanovich Kostomarov (born in 1817 - died in 1885) A classic of Ukrainian historiography. One of the founders of the Cyril and Methodius Society. Among Russian and Ukrainian historians, Nikolai Ivanovich Kostomarov occupies a very special place. This man was

From the book Great Soviet Encyclopedia (FU) of the author TSBFuss Nikolay Ivanovich Fuss Nikolay Ivanovich (29.1.1755, Basel, - 23.12.1825, Petersburg), Russian mathematician. In 1773, at the invitation of L. Euler, he moved to Russia. From 1776 an adjunct, from 1783 an ordinary academician of the Petersburg Academy of Sciences; since 1800 indispensable secretary of the academy. Most of it

From the book Big Dictionary of Quotes and Expressions the author Dushenko Konstantin VasilievichGNEDICH, Nikolai Ivanovich (1784-1833), poet, translator 435 ... Pushkin, Proteus By your flexible tongue and magic? "To Pushkin, after reading his fairy tale about Tsar Saltan ..." (1832)? Gnedich N.I. Poems. - L., 1956, p. 148 Then in V. Belinsky: "Pushkin's genius-proteus"

Nikolai Ivanovich Kostomarov - Russian historian, ethnographer, publicist, literary critic, poet, playwright, public figure, corresponding member of the Imperial St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences, author of the multivolume publication "Russian history in the biographies of its leaders", researcher of the socio-political and economic history of Russia and the modern territory of Ukraine, called by Kostomarov "southern Russia" or "southern edge". Pan-Slavist.

Biography of N.I. Kostomarova

Family and ancestors

|

N.I. Kostomarov |

Nikolai Ivanovich Kostomarov was born on May 4 (16), 1817 in the Yurasovka estate (Ostrogozhsky district, Voronezh province), died on April 7 (19), 1885 in St. Petersburg.

The Kostomarov family is noble, Great Russian. The boyar's son Samson Martynovich Kostomarov, who served in the oprichnina of John IV, fled to Volyn, where he received an estate, which passed to his son, and then to his grandson Peter Kostomarov. Peter in the second half of the 17th century participated in Cossack uprisings, fled to the Moscow state and settled in the so-called Ostrogozhchina. One of the descendants of this Kostomarov in the 18th century married the daughter of the official Yuri Blum and received the Yurasovka settlement (Ostrogozhsky district of the Voronezh province) as a dowry, which was inherited by the historian's father, Ivan Petrovich Kostomarov, a wealthy landowner.

Ivan Kostomarov was born in 1769, served in the military service and, having retired, settled in Yurasovka. Having received a poor education, he tried to develop himself by reading, reading "with a dictionary" exclusively French books of the eighteenth century. I read to the point that I became a convinced "Voltairean", that is, a supporter of education and social equality. Later N.I. Kostomarov in his "Autobiography" wrote about the addictions of a parent:

Everything that we know today about childhood, family and early years of N.I. Kostomarov is drawn exclusively from his "Autobiographies", written by the historian in different versions already in his declining years. These wonderful, in many ways works of art, in places resemble an adventure novel of the 19th century: very original types of heroes, an almost detective plot with murder, the subsequent, absolutely fantastic remorse of criminals, etc. Due to the lack of reliable sources, it is practically impossible to separate the truth from childhood impressions, as well as from the author's later fantasies. Therefore, we will follow what N.I. Kostomarov himself considered necessary to inform his descendants about himself.

According to the historian's autobiographical notes, his father was a tough, wayward, extremely hot-tempered man. Under the influence of French books, he did not put the dignity of nobility into anything and, in principle, did not want to be related to noble families. So, being already in his old years, Kostomarov Sr. decided to marry and chose a girl from his serfs - Tatyana Petrovna Mylnikova (in some publications - Melnikova), whom he sent to study in Moscow, to a private boarding school. It was in 1812, and the Napoleonic invasion prevented Tatyana Petrovna from getting an education. For a long time, among the Yurasov peasants, there lived a romantic legend about how "old Kostomar" drove the best three horses to save his former maid Tanyusha from burning Moscow. Tatyana Petrovna was clearly not indifferent to him. However, soon the courtyards turned Kostomarov against his serf. The landowner was in no hurry to marry her, and his son Nikolai, being born even before the official marriage between his parents, automatically became his father's serf.

Until the age of ten, the boy was brought up at home, according to the principles developed by Rousseau in his "Emile", in the bosom of nature, and from childhood he fell in love with nature. His father wanted to make him a freethinker, but his mother's influence kept him religious. He read a lot and, thanks to his outstanding abilities, easily assimilated what he read, and an ardent fantasy made him experience what he got to know from books.

In 1827, Kostomarov was sent to Moscow, to the boarding school of Mr. Ge, a lecturer in French at the University, but soon, due to illness, he was taken home. In the summer of 1828, young Kostomarov was supposed to return to the boarding house, but on July 14, 1828, his father was killed and robbed by the courtiers. For some reason, the father did not manage to adopt Nicholas in 11 years of his life, therefore, born out of wedlock, as a serf father, the boy was now inherited by his closest relatives - the Rovnevs. When the Rovnevs offered Tatyana Petrovna a widow's share for 14 thousand dessiatines of fertile land - 50 thousand rubles in banknotes, as well as freedom to her son, she agreed without delay.

The murderers of I.P. Kostomarov presented the whole case as if an accident had occurred: the horses were carried, the landowner allegedly fell out of the cage and died. The loss of a large amount of money from his casket became known later, so no police inquiry was made. The true circumstances of the elder Kostomarov's death were revealed only in 1833, when one of the murderers, the lordly coachman, suddenly repented and pointed out to the police his accomplices, lackeys. N.I. Kostomarov wrote in his "Autobiography" that when the guilty began to be interrogated in court, the coachman said: “The master himself is to blame for tempting us; used to start telling everyone that there is no God, that there will be nothing in the next world, that only fools are afraid of the afterlife punishment - we have taken it into our heads that if nothing will happen in the next world, then everything can be done ... "

Later, the servants, stuffed with "Voltairean sermons", brought the robbers to the house of N.I. Kostomarov's mother, who was also robbed clean.

Left with little funds, T.P. Kostomarova sent her son to a rather poor boarding school in Voronezh, where he learned little in two and a half years. In 1831, his mother transferred Nikolai to the Voronezh gymnasium, but even here, according to Kostomarov's recollections, the teachers were bad and unscrupulous, they gave him little knowledge.

After graduating from a course in a gymnasium in 1833, Kostomarov entered first at Moscow, and then at Kharkov University at the Faculty of History and Philology. Professors at that time in Kharkov were unimportant. For example, Russian history was read by Gulak-Artyomovsky, although he was a well-known author of Little Russian poems, but distinguished, according to Kostomarov, in his lectures with empty rhetoric and bombast. However, Kostomarov studied diligently even with such teachers, but, as often happens with young people, he succumbed by nature to one or another hobby. So, settling with the professor of the Latin language P.I. Sokalsky, he began to study classical languages and was especially carried away by the Iliad. V. Hugo's works turned him to the French language; then he began to study the Italian language, music, began to write poetry, and led an extremely chaotic life. He constantly spent his holidays in his village, fond of horse riding, boating, hunting, although his natural myopia and compassion for animals interfered with the last lesson. In 1835, young and talented professors appeared in Kharkov: A.O. Valitsky on Greek literature and M.M. Lunin, who lectured very fascinatingly, on general history. Under the influence of Lunin, Kostomarov began to study history, spent days and nights reading all kinds of historical books. He settled at Artyomovsky-Gulak and now led a very withdrawn lifestyle. Among his few friends was then A. L. Meshlinsky, a well-known collector of Little Russian songs.

The beginning of the way

In 1836, Kostomarov graduated from the course at the university as a full-time student, lived with Artyomovsky for some time, teaching history to his children, then passed the candidate exam and then entered the Kinburn Dragoon Regiment as a cadet.

Kostomarov did not like the service in the regiment; with his comrades, due to the different mentality of their life, he did not become close. Carried away by the analysis of the affairs of the rich archive located in Ostrogozhsk, where the regiment was stationed, Kostomarov often skimped on service and, on the advice of the regimental commander, left it. After working in the archive all summer of 1837, he compiled a historical description of the Ostrogozhsk suburb regiment, attached many copies of interesting documents to it, and prepared it for publication. Kostomarov hoped to compose the history of the entire Sloboda Ukraine in the same way, but did not have time. His work disappeared during the arrest of Kostomarov, and it is not known where he is and even whether he survived at all. In the autumn of the same year, Kostomarov returned to Kharkov, again began to listen to Lunin's lectures and study history. Already at this time, he began to think about the question: why is there so little said in history about the masses? Wanting to understand folk psychology for himself, Kostomarov began to study the monuments of folk literature in the publications of Maksimovich and Sakharov, he was especially carried away by Little Russian folk poetry.

Interestingly, until the age of 16, Kostomarov had no idea about Ukraine and, in fact, about the Ukrainian language. He only learned about the existence of the Ukrainian (Little Russian) language at Kharkov University. When in the years 1820-30 in Little Russia they began to be interested in the history and life of the Cossacks, this interest was most clearly manifested among representatives of the educated society of Kharkov, and especially in the university environment. Here, at the same time, the influence on the young Kostomarov of Artyomovsky and Meshlinsky, and partly of the Russian-language stories of Gogol, in which the Ukrainian flavor is lovingly presented. "Love for the Little Russian word carried me more and more," wrote Kostomarov, "I was annoyed that such a beautiful language remained without any literary processing and, moreover, was subjected to completely undeserved contempt."

An important role in the "Ukrainization" of Kostomarov belongs to II Sreznevsky, then a young lecturer at Kharkov University. Sreznevsky, although a Ryazan by birth, also spent his youth in Kharkov. He was a connoisseur and lover of Ukrainian history and literature, especially after he had visited the places of the former Zaporozhye and had heard a lot of its legends. This gave him the opportunity to compose "Zaporozhye Antiquity".

The rapprochement with Sreznevsky had a strong effect on the novice historian Kostomarov, strengthening his desire to study the peoples of Ukraine, both in the monuments of the past and in present life. For this purpose, he constantly made ethnographic excursions in the vicinity of Kharkov, and then and further. At the same time, Kostomarov began to write in the Little Russian language - first Ukrainian ballads, then the drama "Sava Chaly". The drama was published in 1838, and the ballads a year later (both under the pseudonym "Jeremiah Galka"). The drama drew a flattering review from Belinsky. In 1838, Kostomarov was in Moscow and listened to Shevyrev's lectures there, thinking to take the exam for the master of Russian literature, but fell ill and returned to Kharkov, having managed to study German, Polish and Czech languages and publish his Ukrainian-language works during this time.

Dissertation by N.I. Kostomarov

In 1840 N.I. Kostomarov passed the exam for the master of Russian history, and the next year he presented his thesis "On the meaning of union in the history of Western Russia." In anticipation of a dispute, he went to the Crimea for the summer, which he examined in detail. Upon his return to Kharkov, Kostomarov became close to Kvitka and also to a circle of Little Russian poets, among whom was Korsun, who published the collection "Snin". In the collection, Kostomarov, under the former pseudonym, published poetry and a new tragedy "No Pereyaslavskaya".

Meanwhile, the Kharkiv Archbishop Innokenty drew the attention of the higher authorities to the dissertation already published by Kostomarov in 1842. On the instructions of the Ministry of Public Education, Ustryalov made its assessment and recognized it as unreliable: Kostomarov's conclusions regarding the emergence of the union and its significance did not correspond to the generally accepted ones, which were considered mandatory for Russian historiography of this issue. The case got such a turn that the dissertation was burned and copies of it now constitute a great bibliographic rarity. However, in a revised form, this dissertation was later published twice, although under different names.

The story with the dissertation could have ended Kostomarov's career as a historian forever. But there were generally good reviews about Kostomarov, including from Archbishop Innokenty himself, who considered him a deeply religious person and knowledgeable in spiritual matters. Kostomarov was allowed to write a second dissertation. The historian chose the topic "On the Historical Significance of Russian Folk Poetry" and wrote this essay in 1842-1843, being an assistant inspector of students at Kharkov University. He often visited the theater, especially the Little Russian, placed in the collection "Molodik" Betsky little Russian poems and his first articles on the history of Little Russia: "The first wars of Little Russian Cossacks with the Poles", etc.

Leaving his post at the university in 1843, Kostomarov became a history teacher at the Zimnitsky men's boarding school. Then he already began to work on the story of Bohdan Khmelnytsky. On January 13, 1844, Kostomarov, not without incident, defended his dissertation at Kharkov University (it was also later published in a heavily revised form). He became a master of Russian history and first lived in Kharkov, working on the history of Khmelnitsky, and then, not receiving a department here, asked to serve in the Kiev educational district in order to be closer to the place of his hero's activity.

N.I.Kostomarov as a teacher

In the fall of 1844, Kostomarov was appointed a history teacher at a gymnasium in the city of Rivne, Volyn province. On the way, he visited Kiev, where he met with the reformer of the Ukrainian language and publicist P. Kulish, with the assistant trustee of the educational district M. V. Yuzefovich and other progressive-minded people. In Rovno, Kostomarov taught only until the summer of 1845, but he acquired the common love of both students and comrades for his humanity and excellent presentation of the subject. As always, he used every free time to make excursions to numerous historical areas of Volyn, to make historical and ethnographic observations and to collect monuments of folk art; such were delivered to him by his disciples; all these materials collected by him were printed much later - in 1859.

Acquaintance with the historical places gave the historian the opportunity to later vividly depict many episodes from the history of the first Pretender and Bohdan Khmelnytsky. In the summer of 1845, Kostomarov visited the Holy Mountains, in the fall he was transferred to Kiev as a history teacher at the 1st gymnasium, and then he taught in different boarding schools, including in women - de Mellian (Robespierre's brother) and Zalesskaya (the widow of the famous poet), and later at the Institute of Noble Maidens. His pupils and pupils recalled with delight about his teaching.

Here is what the famous painter Ge reports about him as a teacher:

|

"N. I. Kostomarov was the favorite teacher of all; there was not a single student who did not listen to his stories from Russian history; he made almost the whole city fall in love with Russian history. When he ran into the classroom, everything froze, as in a church, and the living, rich in pictures, the old life of Kiev poured, everyone turned into a hearing; but - a call, and everyone was sorry, both the teacher and the students, that the time had passed so quickly. The most passionate listener was our fellow Pole ... Nikolai Ivanovich never asked much, never gave points; it used to be our teacher tossed us a piece of paper and said quickly: “Here, we need to give points. So you do it yourself, ”he says; and what - no one was given more than 3 points. I’m ashamed, but there were up to 60 people here. Kostomarov's lessons were spiritual holidays; everyone was waiting for his lesson. The impression was that the teacher who took his place in our last grade did not read history for a whole year, but read Russian authors, saying that after Kostomarov he would not read history to us. He made the same impression in the women's boarding school, and then at the University. " |

Kostomarov and Cyril and Methodius Society

In Kiev, Kostomarov became close with several young Little Russians, who formed a circle part of the Pan-Slavic, part of the national trend. Imbued with the ideas of Pan-Slavism, which was then emerging under the influence of the works of Shafarik and other famous Western Slavists, Kostomarov and his comrades dreamed of uniting all Slavs in the form of a federation, with independent autonomy of the Slavic lands, into which the peoples inhabiting the empire were to be distributed. Moreover, the projected federation was supposed to establish a liberal state structure, as it was understood in the 1840s, with the obligatory abolition of serfdom. A very peaceful circle of intellectual intellectuals, intending to act only by correct means, and, moreover, deeply religious in the person of Kostomarov, had the appropriate name - the Brotherhood of Sts. Cyril and Methodius. He seemed to indicate by this that the activities of the Holy Brothers, religious and educational, dear to all Slavic tribes, can be considered the only possible banner for Slavic unification. The very existence of such a circle at that time was already an illegal phenomenon. In addition, its members, wishing to "play" either conspirators or Masons, deliberately gave their meetings and peaceful conversations the character of a secret society with special attributes: a special icon and iron rings with the inscription: "Cyril and Methodius". The brotherhood also had a seal on which it was engraved: "Understand the truth, and the truth will set you free." Af. V. Markovich, later a famous South Russian ethnographer, writer N. I. Gulak, poet A. A. Navrotsky, teachers V. M. Belozersky and D. P. Pilchikov, several students, and later T. G. Shevchenko, on whose work the ideas of the Pan-Slavic brotherhood were so reflected. Occasional "brothers" also attended meetings of the society, for example, the landowner N. I. Savin, who was familiar to Kostomarov from Kharkov. The notorious publicist P.A.Kulish also knew about the brotherhood. With his peculiar humor, he signed some of his messages to members of the brotherhood "Hetman Panka Kulish". Subsequently, in the III-rd department, this joke was estimated at three years of exile, although the "hetman" Kulish himself was not officially a member of the brotherhood. Just so it’s clear ...

June 4, 1846 N.I. Kostomarov was elected an adjunct in Russian history at Kiev University; classes in the gymnasium and other boarding schools, he now left. His mother also settled in Kiev with him and sold the part of Yurasovka that she had inherited.

Kostomarov was a professor at Kiev University for less than a year, but the students, with whom he behaved simply, loved him very much and were fond of his lectures. Kostomarov read several courses, including Slavic mythology, which he printed in Church Slavonic script, which was partly the reason for its prohibition. Only in the 1870s were copies printed 30 years ago put on sale. Kostomarov also worked on Khmelnitsky, using materials available in Kiev and the famous archaeologist Gr. Svidzinsky, and was also elected a member of the Kiev Commission for the analysis of ancient acts and prepared the chronicle of S. Velichka for publication.

At the beginning of 1847, Kostomarov became engaged to Anna Leontievna Kragelskaya, his student from the boarding house of de Mellan. The wedding was scheduled for March 30th. Kostomarov was actively preparing for family life: he looked after a house for himself and the bride on Bolshaya Vladimirskaya, closer to the university, and ordered a piano for Alina from Vienna itself. After all, the historian's bride was an excellent performer - Franz Liszt himself admired her performance. But ... the wedding did not take place.

On the denunciation of student A. Petrov, who overheard Kostomarov's conversation with several members of the Cyril and Methodius Society, Kostomarov was arrested, interrogated and sent under the protection of gendarmes to the Podolsk unit. Then, two days later, he was brought to say goodbye to his mother's apartment, where Alina Kragelskaya's bride, all in tears, was waiting.

“The scene was tearing apart,” wrote Kostomarov in his Autobiography. “Then they put me on the checkpoint and took me to Petersburg ... The state of my spirit was so deadly that I had the idea to starve myself to death on the way. I refused all food and drink and had the firmness to travel in this way for 5 days ... My guide from the quarter realized what was in my mind and began to advise me to leave my intention. “You,” he said, “will not inflict death on yourself, I will have time to drive you, but you will hurt yourself: they will start interrogating you, and delirium will become with you from exhaustion, and you will say too much about yourself and others.” Kostomarov listened to the advice.

In St. Petersburg the chief of the gendarmes, Count Alexei Orlov, and his assistant, Lieutenant General Dubelt, talked to the arrested person. When the scientist asked permission to read books and newspapers, Dubelt said: "You can't, my good friend, you have read too much."

Soon, both generals found out that they were dealing not with a dangerous conspirator, but with a romantic dreamer. But the investigation dragged on all spring, as the case was hampered by their "intractability" by Taras Shevchenko (he received the most severe punishment) and Nikolai Gulak. There was no court. Kostomarov learned the Tsar's decision on May 30 from Dubelt: a year of imprisonment in a fortress and an indefinite exile "to one of the distant provinces." Kostomarov spent a year in the 7th chamber of the Alekseevsky ravelin, where his already not very good health suffered greatly. However, the mother was allowed to the prisoner, books were given and, by the way, he learned ancient Greek and Spanish there.

The historian's wedding with Alina Leontyevna was finally upset. The bride herself, being a romantic nature, was ready, like the wives of the Decembrists, to follow Kostomarov anywhere. But to her parents, marriage to a "political criminal" seemed inconceivable. At the insistence of her mother, Alina Kragelskaya married an old friend of their family, the landowner M. Kisel.

Kostomarov in exile

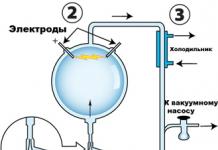

“For the compilation of a secret society, in which the unification of the Slavs into one state was discussed,” Kostomarov was sent to serve in Saratov, with a ban on printing his works. Here he was appointed a translator of the Provincial Government, but he had nothing to translate, and the governor (Kozhevnikov) entrusted him with managing, first, a criminal, and then a secret table, where mainly schismatic cases were carried out. This gave the historian the opportunity to thoroughly familiarize himself with the schism and, although not without difficulty, to become close to its followers. Kostomarov published the results of his studies of local ethnography in Saratov Provincial Gazette, which he temporarily edited. He also studied physics and astronomy, tried to make a balloon, even engaged in spiritualism, but did not stop studying the history of Bohdan Khmelnitsky, receiving books from Gr. Svidzinsky. In exile, Kostomarov began to collect materials for studying the inner life of pre-Petrine Russia.

In Saratov, near Kostomarov, a circle of educated people was grouped, partly from exiled Poles, partly from Russians. In addition, Archimandrite Nikanor, later the archbishop of Kherson, II Palimpsestov, later a professor at Novorossiysk University, EA Belov, Varentsov, and others were close to him in Saratov; later N. G. Chernyshevsky, A. N. Pypin and especially D. L. Mordovtsev.

In general, Kostomarov's life in Saratov was not bad at all. Soon his mother came here, the historian himself gave private lessons, made excursions, for example, to the Crimea, where he participated in the excavation of one of the Kerch mounds. Later, the exiled quite calmly left for Dubovka to get acquainted with the schism; to Tsaritsyn and Sarepta - to collect materials about the Pugachev region, etc.

In 1855, Kostomarov was appointed clerk of the Saratov Statistical Committee, and published many articles on Saratov statistics in local publications. The historian collected a lot of materials on the history of Razin and Pugachev, but did not process them himself, but transferred them to D.L. Mordovtsev, who then, with his permission, used them. Mordovtsev at this time became Kostomarov's assistant on the statistical committee.

At the end of 1855, Kostomarov was allowed to go on business to St. Petersburg, where he worked for four months in the Public Library on the Khmelnitsky era, and on the inner life of ancient Russia. At the beginning of 1856, when the ban on publishing his works was lifted, the historian published in Otechestvennye Zapiski an article about the struggle of Ukrainian Cossacks with Poland in the first half of the 17th century, constituting a preface to his Khmelnytsky. In 1857, "Bogdan Khmelnitsky" finally appeared, albeit in an incomplete version. The book made a strong impression on contemporaries, especially with its artistic presentation. Indeed, before Kostomarov, none of the Russian historians turned seriously to the history of Bohdan Khmelnitsky. Despite the unprecedented success of the study and positive reviews about it in the capital, the author still had to return to Saratov, where he continued to study the inner life of ancient Russia, especially on the history of trade in the 16th-17th centuries.

The coronation manifesto freed Kostomarov from supervision, but the order prohibiting him from serving in the academic part remained in force. In the spring of 1857, he arrived in St. Petersburg, submitted his research on the history of trade to print, and went abroad, where he visited Sweden, Germany, Austria, France, Switzerland and Italy. In the summer of 1858, Kostomarov again worked in the St. Petersburg Public Library on the history of Stenka Razin's rebellion and, at the same time, wrote, on the advice of NV Kalachov, with whom he became close then, the story "Son" (published in 1859); he also saw Shevchenko, who had returned from exile. In the fall, Kostomarov took the place of a clerk in the Saratov Provincial Committee on Peasant Affairs and thus connected his name with the liberation of the peasants.

Scientific, teaching, publishing activities of N.I. Kostomarova

At the end of 1858, N.I.Kostomarov's monograph "The Riot of Stenka Razin" was published, which finally made his name famous. The works of Kostomarov had, in a sense, the same meaning as, for example, Shchedrin's Provincial Essays. They were the first scientific works on Russian history in time, in which many issues were considered not according to the template of the official scientific direction, which was not obligatory until then; at the same time they were written and presented wonderfully artistically. In the spring of 1859, St. Petersburg University elected Kostomarov an extraordinary professor of Russian history. After waiting for the closure of the Committee on Peasant Affairs, Kostomarov, after a very cordial send-off in Saratov, came to St. Petersburg. But then it turned out that the case about his professorship did not work out, it was not approved, for the Tsar was informed that Kostomarov had written an unreliable essay about Stenka Razin. However, the Emperor himself read this monograph and spoke very favorably of it. At the request of brothers D.A. and N.A. Milyutin, Alexander II allowed N.I. Kostomarov as a professor, only not at Kiev University, as planned earlier, but at St. Petersburg.

Kostomarov's introductory lecture took place on November 22, 1859 and caused a thunderous ovation from the students and the audience. Professor of St. Petersburg University Kostomarov did not stay long (until May 1862). But even during this short time, he became known as a talented teacher and an outstanding lecturer. Several very respectable figures in the field of the science of Russian history emerged from Kostomarov's students, for example, Professor A.I. Nikitsky. The fact that Kostomarov was a great artist-lecturer, many memories of his students have survived. One of Kostomarov's listeners said this about his reading:

|

“Despite his rather motionless appearance, his quiet voice and not quite clear, lisping accent with a very noticeable pronunciation of words in the Little Russian way, he read remarkably. Whether he portrayed the Novgorod veche or the tumult of the Lipetsk battle, he had to close his eyes - and after a few seconds he seemed to be transported to the center of the depicted events, you see and hear everything that Kostomarov is talking about, who meanwhile stands motionless in the pulpit; his gaze is not looking at the listeners, but somewhere into the distance, as if it is something that is seeing clearly at this moment in the distant past; the lecturer even seems to be a person not of this world, but a native of the other world, who appeared on purpose in order to inform about the past, mysterious to others, but so well known to him. " |

In general, Kostomarov's lectures greatly influenced the public's imagination, and his fascination with them can be partly explained by the lecturer's strong emotionality, constantly breaking through, despite his outward calmness. She literally "infected" the listeners. After each lecture, the professor was given a standing ovation, he was carried in his arms, etc. At St. Petersburg University, N.I. Kostomarov taught the following courses: History of Ancient Rus (from which an article was published on the origin of Rus with the Zhmud theory of this origin); ethnography of foreigners who lived in antiquity in Russia, starting with the Lithuanians; the history of the Old Russian regions (part of it was published under the title "Northern Russian People's Rights"), and historiography, from which only the beginning was printed, devoted to the analysis of the chronicles.

In addition to university lectures, Kostomarov also read public ones, which also enjoyed tremendous success. In parallel with his professorship, Kostomarov worked with sources, for which he constantly visited both St. Petersburg and Moscow and provincial libraries and archives, examined the ancient Russian cities of Novgorod and Pskov, and more than once traveled abroad. The public dispute between N.I. Kostomarov and M.P. Pogodin over the issue of the origin of Rus also belongs to this time.

In 1860, Kostomarov became a member of the Archaeographic Commission, with the assignment to edit the acts of southern and western Russia, and was elected a full member of the Russian Geographical Society. The Commission published 12 volumes of acts under his editorship (from 1861 to 1885), and the Geographical Society published three volumes of "Proceedings of the Ethnographic Expedition to the West Russian Territory" (III, IV and V - in 1872-1878).

In St. Petersburg, near Kostomarov, a circle was formed, to which belonged: Shevchenko, however, who soon died, the Belozerskys, the bookseller Kozhanchikov, A. A. Kotlyarevsky, ethnographer S. V. Maksimov, astronomer A. N. Savich, priest Opatovich and many others. This circle in 1860 began to publish the Osnova magazine, in which Kostomarov was one of the most important collaborators. Here are published his articles: "On the federal beginning of ancient Russia", "Two Russian nationalities", "Features of the South Russian history" and others, as well as many polemical articles about attacks on him for "separatism", "Ukrainophilism", " anti-Normanism ", etc. He also took part in the publication of popular books in the Little Russian language (" Metelikov "), and for the publication of Holy Scripture he collected a special fund, which was later used for the publication of the Little Russian dictionary.

"Duma" incident

At the end of 1861, due to student unrest, St. Petersburg University was temporarily closed. Five "instigators" of the riots were expelled from the capital, 32 students were expelled from the university with the right to take final exams.

On March 5, 1862, P.V. Pavlov, a public figure, historian and professor at St. Petersburg University, was arrested and administratively exiled to Vetluga. He did not give a single lecture at the university, but at a public reading in favor of writers in need, he ended his speech on the millennium of Russia with the following words:

In protest against the repression of students and the expulsion of Pavlov, the professors of St. Petersburg University Kavelin, Stasyulevich, Pypin, Spasovich, Utin resigned.

Kostomarov did not support the protest against Pavlov's expulsion. In this case, he went the "middle way": he offered to continue classes for all students wishing to study and not hold a meeting. To replace the closed university, due to the efforts of professors, including Kostomarov, a “free university”, as they said at the time, was opened in the hall of the City Duma. Kostomarov, despite all the persistent "requests" and even intimidation from the radical student committees, began to lecture there.

The "advanced" students and some of the professors who followed him, in protest against Pavlov's expulsion, demanded the immediate closure of all lectures in the City Duma. They decided to announce this action on March 8, 1862, right after the crowded lecture by Professor Kostomarov.

A participant in the student riots of 1861-62, and in the future, the famous publisher L.F. Panteleev, in his memoirs, describes this episode as follows:

|

“It was March 8, the big Duma hall was overcrowded not only with students, but also with a huge mass of the public, as rumors about some forthcoming demonstration had already penetrated into it. Now Kostomarov finished his lecture; the usual applause rang out. Then the student E.P. Pechatkin immediately entered the department and made a statement about the closure of the lectures with the same reasoning that was established at the meeting with Spasovich, and with a reservation about the professors who would continue the lectures. Kostomarov, who did not have time to move far from the department, immediately returned and said: "I will continue to lecture," and at the same time added a few words that science should go its own way, not getting entangled in various everyday circumstances. At once there were applause and booing; but here under the very nose of Kostomarov E. Utin blurted out: “Scoundrel! second Chicherin [B. N. Chicherin then published, it seems, in Moskovskiye Vedomosti (1861, Nos. 247,250 and 260), a number of reactionary articles on the university question. But even earlier, his letter to Herzen made the name of BN extremely unpopular among young people; Kavelin defended him, seeing in him a great scientific value, although he did not share most of his views. (Approx. L. F. Panteleev)], Stanislav on the neck! " The influence enjoyed by N. Utin apparently haunted E. Utin, and he then climbed out of his skin to declare his extreme radicalism; he was even jokingly nicknamed Robespierre. E. Utin's trick could blow up even a less impressionable person than Kostomarov; unfortunately, he lost all composure and, returning to the pulpit again, said, among other things: “... I don’t understand those gladiators who want to please the public with their sufferings (whom he meant understandable as an allusion to Pavlov). I see the Repetilovs in front of me, of whom the Rasplyuevs will emerge in a few years. " There was no more applause, but it seemed that the whole hall was hissing and whistling ... " |

When this egregious case became known in wider public circles, it caused deep disapproval both among the university professors and among the students. Most of the teachers decided to continue giving lectures without fail - now out of solidarity with Kostomarov. At the same time, indignation at the historian's behavior increased among the radical student youth. The adherents of the ideas of Chernyshevsky, the future figures of "Earth and Freedom", unequivocally excluded Kostomarov from the lists of "guardians for the people", having hung the professor as a "reactionary".

Of course, Kostomarov could well have returned to the university and continued teaching, but, most likely, he was deeply offended by the "Duma" incident. Perhaps the elderly professor simply did not want to argue with anyone and once again prove his case. In May 1862 N.I. Kostomarov resigned and left the walls of St. Petersburg University forever.

From that moment on, his break with N.G. Chernyshevsky and those close to him took place. Kostomarov finally goes over to liberal-nationalist positions, not accepting the ideas of radical populism. According to the people who knew him at that time, after the events of 1862, Kostomarov seemed to have “lost interest” in modernity, completely turning to the subjects of the distant past.

In the 1860s, Kiev, Kharkov and Novorossiysk universities tried to invite a historian to be their professors, but, according to the new university charter of 1863, Kostomarov did not have formal rights to a professorship: he was only a master's degree. Only in 1864, after he published the essay "Who was the first impostor?", Kiev University gave him a doctorate honoris causa (without defending his doctoral dissertation). Later, in 1869, St. Petersburg University elected him an honorary member, but Kostomarov never returned to teaching. In order to provide financial support for the outstanding scientist, he was assigned the corresponding salary of an ordinary professor for his service in the Archaeographic Commission. In addition, he was a corresponding member of the II Department of the Imperial Academy of Sciences and a member of many Russian and foreign scientific societies.

Leaving the university, Kostomarov did not abandon his scientific activities. In the 1860s, he published "North Russian People's Rights", "History of the Time of Troubles", "Southern Russia at the end of the 16th century." (alteration of the destroyed dissertation). For research "The last years of the Commonwealth" ("Bulletin of Europe", 1869. Book 2-12) N.I. Kostomarov was awarded the Academy of Sciences Prize (1872).

last years of life

In 1873, after a trip to Zaporozhye, N.I. Kostomarov visited Kiev. Here he quite by chance found out that his former bride, Alina Leontyevna Kragelskaya, by that time already widowed and bearing the name of her late husband, Kisel, was living in the city with her three children. This news deeply moved the 56-year-old Kostomarov, who was already exhausted by his life. Having received the address, he immediately wrote a short letter to Alina Leontyevna asking for a meeting. The answer was yes.

They met 26 years later, like old friends, but the joy of a date was overshadowed by thoughts of lost years.

“Instead of a young girl, as I left her, - wrote NI Kostomarov, - I found an elderly lady and a sick woman, a mother of three half-grown children. Our meeting was as pleasant as it was sad: we both felt that the best time of our separation had passed irrevocably. "

Over the years, Kostomarov also did not look younger: he has already suffered a stroke, his eyesight has deteriorated significantly. But the former bride and groom did not want to part again after a long separation. Kostomarov accepted Alina Leontyevna's invitation to stay at her estate Dedovtsy, and when he left for St. Petersburg, he took Alina's eldest daughter, Sophia, with him in order to arrange her at the Smolny Institute.

Only difficult life circumstances helped the old friends finally get closer. At the beginning of 1875, Kostomarov fell seriously ill. It was believed to be typhoid, but some doctors suggested, in addition to typhoid, a second stroke. When the patient was delirious, his mother Tatyana Petrovna died of typhus. Doctors for a long time hid her death from Kostomarov - his mother was the only close and dear person throughout the life of Nikolai Ivanovich. Completely helpless in everyday life, the historian could not do without his mother even in trifles: to find a handkerchief in the chest of drawers or light a pipe ...

And at that moment Alina Leontyevna came to the rescue. Having learned about the plight of Kostomarov, she gave up all her affairs and came to St. Petersburg. Their wedding took place already on May 9, 1875 in the estate of Alina Leontyevna Dedovtsy of the Priluksky district. The newlywed was 58 years old, and his chosen one was 45. Kostomarov adopted all the children of A.L. Kissel from the first marriage. The wife's family became his family as well.

Alina Leontyevna not only replaced Kostomarov's mother, taking over the organization of the life of the famous historian. She became an assistant in work, a secretary, a reader and even an adviser in scientific affairs. Kostomarov wrote and published his most famous works when he was already a married man. And in this there is a share of participation of his wife.

Since then, the historian spent the summer almost constantly in the village of Dedovtsi, 4 versts from the town of Priluk (Poltava province) and at one time was even an honorary trustee of the Prilutsk men's gymnasium. In the winter he lived in St. Petersburg, surrounded by books and continued to work, despite the breakdown and almost complete loss of sight.

Among the latest works, he can be called "The Beginning of Autocracy in Ancient Rus" and "On the Historical Significance of Russian Song Folk Art" (revision of the master's thesis). The beginning of the second was published in the magazine "Beseda" for 1872, and the continuation was partly in "Russian Mysl" for 1880 and 1881 under the title "History of the Cossacks in the monuments of South Russian folk songwriting." Part of this work was included in the book "Literary Heritage" (St. Petersburg, 1890) under the title "Family Life in the Works of South Russian Folk Song Creativity"; a part was simply lost (see "Kievskaya Starina", 1891, No. 2, Documents, etc. Art. 316). The end of this large-scale work was not written by the historian.

At the same time, Kostomarov wrote "Russian History in the Biographies of its Main Figures", which was also unfinished (ends with the biography of Empress Elizabeth Petrovna) and major works on the history of Little Russia, as a continuation of previous works: "Ruin", "Mazepa and Mazepa", "Pavel Half-work ". Finally, he wrote a number of autobiographies that have more than just personal meaning.

Constantly ill since 1875, Kostomarov was especially damaged by the fact that on January 25, 1884, he was knocked down by the carriage under the arch of the General Staff. Similar cases had happened to him before, for the half-blind, and besides, the historian carried away by his thoughts, often did not notice what was happening around him. But before Kostomarov was lucky: he got off with minor injuries and quickly recovered. The incident of January 25 knocked him down completely. In early 1885, the historian fell ill and died on April 7. He was buried at the Volkovo cemetery on the so-called "literary bridge", a monument was erected on his grave.

Assessment of the personality of N.I. Kostomarov

Outwardly, N.I. Kostomarov was of average height and far from handsome. The boarding school students where he taught as a young man called him a "sea scarecrow." The historian had a surprisingly awkward figure, loved to wear excessively spacious clothes that hung on him like on a hanger, was extremely absent-minded and very short-sighted.

Spoiled from childhood by the excessive attention of his mother, Nikolai Ivanovich was distinguished by complete helplessness (mother all her life tied a tie to her son and handed him a handkerchief), but at the same time, he was unusually capricious in everyday life. This was especially evident in mature years. For example, one of Kostomarov's frequent diners recalled that the elderly historian did not hesitate to be capricious at the table even in the presence of guests: did not see how they killed whitefish or ruffs, or pike perch, and therefore proved that the fish was bought inanimate. Most of all he found fault with the butter, saying that it was bitter, although it was bought in the best store. "

Fortunately, wife Alina Leontyevna had a talent for turning the prose of life into a game. Jokingly, she often called her husband "my old thing" and "my spoiled old man." Kostomarov, in turn, jokingly called her "lady".

Kostomarov's mind was extraordinary, knowledge is very extensive and not only in those areas that served as the subject of his special studies (Russian history, ethnography), but also in such, for example, as theology. Archbishop Nikanor, a well-known theologian, used to say that he did not dare to compare his knowledge of Holy Scripture with that of Kostomarov. Kostomarov's memory was phenomenal. He was a passionate esthetician: he was fond of everything artistic, pictures of nature most of all, music, painting, theater.

Kostomarov was also very fond of animals. They say that while working, he constantly kept his beloved cat next to him on the table. The creative inspiration of the scientist seemed to depend on the fluffy companion: as soon as the cat jumped to the floor and went about his cat business, the feather in Nikolai Ivanovich's hand froze powerlessly ...

Contemporaries condemned Kostomarov for the fact that he always knew how to find some negative quality in a person who was praised in his presence; but, on the one hand, there was always truth in his words; on the other hand, if under Kostomarov they began to speak ill of someone, he almost always knew how to find good qualities in him. In his behavior, a spirit of contradiction was often expressed, but in fact he was extremely gentle and soon forgave those people who were guilty before him. Kostomarov was a loving family man, a devoted friend. His sincere feeling for his failed bride, which he managed to endure through the years and all the trials, cannot but inspire respect. In addition, Kostomarov also possessed extraordinary civic courage, did not renounce his views and convictions, never followed the lead either in power (the story of the Cyril and Methodius Society) or among the radical part of the student body (the "Duma" incident).

Remarkable is Kostomarov's religiosity, stemming not from general philosophical views, but warm, so to speak, spontaneous, close to the religiosity of the people. Kostomarov, who knew well the dogma of Orthodoxy and its morality, was also dear to every feature of church rituals. Attending divine services was for him not just a duty, which he did not shy away from even during a severe illness, but also a great aesthetic pleasure.

Historical conception of N.I. Kostomarov

Historical concepts of N.I. Kostomarov, for more than a century and a half, have been causing ongoing controversy. In the works of researchers, no unambiguous assessment of its multifaceted, sometimes contradictory historical heritage has yet been developed. In the extensive historiography of both the pre-Soviet and Soviet periods, he appears as a peasant, noble, noble-bourgeois, liberal-bourgeois, bourgeois-nationalist and revolutionary-democratic historian at the same time. In addition, there are frequent characteristics of Kostomarov as a democrat, socialist and even a communist (!), Pan-Slavist, Ukrainianophile, federalist, historian of folk life, folk spirit, historian-populist, historian-lover of truth. Contemporaries often wrote about him as a romantic historian, lyric poet, artist, philosopher and sociologist. Descendants, grounded in Marxist-Leninist theory, found that Kostomarov was a historian, weak as a dialectician, but a very serious historian and analyst.

Today's Ukrainian nationalists willingly raised Kostomarov's theories on the shield, finding in them a historical justification for modern political insinuations. Meanwhile, the general historical concept of the long-deceased historian is quite simple and it makes no sense to look for manifestations of nationalist extremism in it, and even more so - attempts to exalt the traditions of one Slavic people and belittle the importance of another - is completely meaningless.

Historian N.I. Kostomarov put the opposition of state and popular principles in the general historical process of development of Russia. Thus, the innovation of his constructions consisted only in the fact that he acted as one of the opponents of the “state school” of S.M. Solovyov and her followers. The state principle was associated by Kostomarov with the centralizing policy of the great princes and tsars, the national principle with the communal principle, the political form of expression of which was the national assembly or veche. It was the veche (and not the communal, as among the “populists”) principle that embodied in N.I. Kostomarov, the system of federal structure that most corresponded to the conditions of Russia. This system made it possible to maximize the potential of the people's initiative - the true driving force of history. The state-centralizing principle, according to Kostomarov, acted as a regressive force that weakened the active creative potential of the people.

According to Kostomarov's concept, the main driving forces that influenced the formation of Muscovite Rus were two principles - autocratic and specific veche. Their struggle ended in the 17th century with the victory of the great power principle. The specific-veche beginning, according to Kostomarov, “was clothed in a new image,” that is, the image of the Cossacks. And the uprising of Stepan Razin became the last battle of the people's democracy with the victorious autocracy.

The personification of the autocratic principle in Kostomarov is precisely the Great Russian people, i.e. a set of Slavic peoples who inhabited the northeastern lands of Russia before the Tatar invasion. The South Russian lands were less affected by foreign influence, and therefore managed to preserve the traditions of people's self-government and federal preferences. In this regard, Kostomarov's article "Two Russian Nationalities" is very characteristic, which states that the South Russian nationality has always been more democratic, while the Great Russian has other qualities, namely, a creative beginning. The Great Russian nationality created a monarchy (that is, a monarchical system), which gave it priority importance in the historical life of Russia.

The opposite of the "people's spirit" of "southern Russian nature" (in which "there was nothing violent, leveling; there was no politics, there was no cold calculation, firmness on the way to the appointed goal") and "Great Russians" (which are characterized by a slavish willingness to submit to autocratic power, the desire "to give strength and formality to the unity of their land"), in the opinion of N.I. Kostomarov, various directions of development of the Ukrainian and Russian peoples. Even the fact of the flourishing of the veche system in the "northern Russian peoples' rights" (Novgorod, Pskov, Vyatka) and the establishment of a monarchical system in the southern regions of N.I. Kostomarov explained by the influence of the "South Russians", who allegedly founded the North Russian centers with their veche freemen, while such a freeman in the south was suppressed by the northern autocracy, breaking through only in the way of life and love of freedom of the Ukrainian Cossacks.

Even during his lifetime, the "statesmen" hotly accused the historian of subjectivism, the desire to absolutize the "popular" factor in the historical process of the formation of statehood, as well as the deliberate opposition of the contemporary scientific tradition.

Opponents of "Ukrainianization", in turn, even then attributed to Kostomarov nationalism, justification of separatist tendencies, and in his enthusiasm for the history of Ukraine and the Ukrainian language they saw only a tribute to the Pan-Slavist fashion that captured the best minds of Europe.

It will not be superfluous to note that in the works of N.I. Kostomarov, there are absolutely no clear indications of what should be perceived with a plus sign and what should be displayed as a minus sign. Nowhere does he unequivocally condemn autocracy, recognizing its historical expediency. Moreover, the historian does not say that specific-vechevaya democracy is unambiguously good and acceptable for the entire population of the Russian Empire. It all depends on the specific historical conditions and characteristics of the character of each nation.